|

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Nora Claire Miller is a poet from New York City. Nora is the author of the chapbook LULL (2020). Their poems have appeared or are forthcoming in FENCE, Bennington Review, Washington Square Review, Bat City Review, Tagvverk, and other places. The editor-in-chief of Ghost Proposal, Nora earned an MFA from the Iowa Writers' Workshop and a BA from Hampshire College. Your poems are immensely fun and so different from the overwhelmingly archaic poetry that is taught in school classrooms. When did you realize that poetry can be more than traditional writing about serious subject matters and can exist outside of print form?

Thanks so much for the compliment—that means a lot! It's an interesting question. Working in visual and hybrid forms has always felt, for me, like a way to express my frustration with traditional structures. I think the first time I intentionally wrote a visual poem was in sixth grade. My English teacher had asked our class to write and curate a portfolio of ten poems. By curate, I think she actually meant we should type them up and print them out in a nice font. But it was the end of the school year and I was sick of Microsoft Word and following instructions. The teacher hadn't requested a particular format for our poems, so I gathered broken objects from around my family's apartment—bent eyeglasses, an ancient Nokia cell phone, an old wooden clock—and wrote poems on them in Sharpie. Instead of a report, I handed my teacher a large plastic bag full of sculptures. To my utter surprise, my teacher said the poems were "unique" and did not send me to detention. Ten years later, I started my MFA at the Iowa Writers' Workshop. I was going through a period of creative flux, and wasn't sure what kinds of poems I wanted to be writing. Everything I put on the page felt wrong, so I would revise my poems until there was practically no substance left. All of my poems were very short and no one could make any sense of them, not even me. One night, frustrated during an especially challenging revision, I printed out a copy of my poem and deep-fried it on the stove. I took a photograph of this deep-fried poem and submitted it, with no explanation, to that week's workshop packet. Even though I was an adult in an MFA program at that point, I was still a little surprised when I didn't get in any trouble. After that, something broke open for me. I stopped being so afraid of what other people thought of me, and I began to recognize poetry as something that could be physical. Thank you for sharing that, Nora. The story with your English teacher is so endearing. Is that deep-fried poem part of the ones that appeared in phoebe? You titled them “Deep Friend Poem #63” and “Deep Fried Poem #64.” Did you create a series of deep-fried poems? If so, are there sixty-plus more? There are so, so many more—in all, I've deep-fried many hundreds of poems at this point. I have found that like any poem-writing, it's necessary to deep-fry poems in bulk. I am working on a book of full-color photographs of deep-fried poems. In assembling it, I've had to fry far more poems than I have ultimately ended up with. I've found that only half of the poems I deep-fry turn into objects worth recording or preserving, and of those, many break or decay before I can photograph them properly. Then, there are the deep-fried poems that look great in real life but just don't photograph well. It's a tricky business! Wow, that's amazing! I’m so captivated by the uniqueness and ingenuity of each of your works. Do you establish the form of a poem before or after it’s written? To me, the form of a poem is inextricable from its content. If the exterior shape of the poem changes, the language is altered too—either because I have to change the words to fit the particularities of the new shape, or else because their new orientation changes the way they look, sound, and feel. I often shift my poems’ physical shapes as part of my process of revision, because it helps me understand and adjust the ways the words are working together. I don’t think of a poem as finished until I find its final shape. How do you decide if a piece will be visual? Do you approach visual versus non-visual work differently? That’s an interesting question. I think there's an artificial line between the idea of a visual poem and a "non-visual" one. At the end of the day, all poems that are written for the page have shapes and forms we can see. Even if a poet thinks they're making few visual choices in their writing, there's inherent visual work just in placing a poem on a page—patterning of letters, the places we break lines, the fonts we use, the punctuation, the capitalization, caesura. For performance poetry, slam poetry, sound poetry, and other forms that involve the human voice, there's a physicality to that too: sound waves are physical shapes that we create and share with our bodies. That being said, as much as the delineation between visual and non-visual poetry feels arbitrary, it is (like many delineations) nonetheless real in its consequences: there are poems people would call visual art and there are poems people would call "regular poems" and there are things people would call "music" and these things get treated very differently by artists and by poets. The work I make often falls into a muddy category—too cross-disciplinary to be considered "real poetry," but too rooted in language to be considered "real art." I don't really care what my work gets called. Personally, I call all of my works poems, and I approach all of my poems in much the same way: I write something in a shape meant to communicate something. Sometimes a poem begins as a drawing in a notebook, or a screenshot on my phone. Sometimes the visual aspects creep in later, in revision, as I get to know my poem and what it wants a little better. There are, of course, differences between different writing processes. For instance, I recently wrote a poem with a sharpie on the surface of a lava lamp's glass, the text wending around the bottle in a spiral. Unlike a poem typed on a computer, the poem I wrote was not one it would be possible to revise later: it was permanent and thus frozen in time. Reading it requires a more physical action than a poem printed on a page or a screen: the reader has to walk around the lava lamp in a circle in order to read the text in "order." The lava lamp poem sounds brilliant—since it’s three-dimensional, how do you intend it to be exhibited? Would printing it in a traditional literary journal do it justice? I’m also wondering if you have a background in visual arts or design because you frequently play with font and form in your work. Thank you! It was a lot of fun to make. There's something that feels almost wrong about writing on a lava lamp, and I think that’s what gives the process its power. I have taken art classes on and off over the years but don’t have much formal training—at least none that would teach me to do the sort of work I do. Instead, I’ve learned by doing, and by asking the visual artists in my life for advice when I want to do something I don’t know how to. As far as publishing goes, it’s a complicated question. I had the opportunity to show the lava lamp in an art show recently. Art shows or in-person events often become the avenue for works like lava lamp poems or deep-fried poems, because it gives people a chance to fully experience the piece as a material object. On the other hand, if a poem can only be read in-person, it changes the work because it changes the work’s audience. Lit mags, especially online ones, expand access. I recently became Editor-in-Chief of Ghost Proposal, a journal and chapbook press. Our editorial team is working hard to make dimensional, visual, and multidisciplinary poetry more available to a wider audience. Congrats on becoming Editor-in-Chief of Ghost Proposal! How has leading the journal been and where do you envision it going? Thank you! It's been an exciting journey. I first connected with Ghost Proposal when they published my chapbook LULL in 2020. I was deeply grateful to get to work with a press that valued experimental and visual work, and fell in love with their past chapbook catalog and issues. So when the former editors decided to pursue other projects and asked me if I'd like to take over as Editor-in-Chief, of course I said yes! I am joined by two incredible co-editors, Alyssa Moore and Kelly Clare. We're dedicated to furthering Ghost Proposal's mission of publishing cross-disciplinary work that resists categorization by form and genre. We're especially interested in work that sits at the intersection of poetry and visual art. We recently launched the Ultraslant Prize, an annual award for one work of visual poetry; each year, the winning poem will be printed as a pamphlet. There aren't many prizes for this type of work and it's been incredible to be in the position to create opportunities. I'm so happy about the work Ghost Proposal does to uplift visual poetry. You also directed a film, Egg Cream! How did you get into directing? Do you see yourself creating more films in the future? Egg Cream was a film that I made in collaboration with my dad Peter Miller, who is a documentary filmmaker. We started filming when I was eleven years old and finished it over a decade later. The project began, as most things do, with a question: I wanted to know the story behind the chocolate egg cream, a soda drink that is said to have originated among Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Despite its name, the egg cream contains neither eggs nor cream—just milk, chocolate syrup, and seltzer. To better understand the origins and significance of the egg cream, my dad and I took his video camera and wandered New York City, where we lived, trying as many egg creams as we could. We interviewed deli workers, food historians, relatives, and even my Hebrew school teacher. When I was thirteen or so, we put the project on hold, and the tapes sat forgotten in a box for about a decade. When I was in graduate school, we uncovered them and, with the help of the extraordinary film editor Amy Linton, we finally finished the film. Though documentary is not my usual medium, I realized, working on Egg Cream, that the process of telling a story—the inquiry, the conversations, the research, the stitching together—is very similar from one medium to another. As a writer, I love studying films as much as I loved making them—I'm drawn to how a film can weave together elements of image, language, and sound all at once. I think poets can learn a lot from watching (and making) movies.

0 Comments

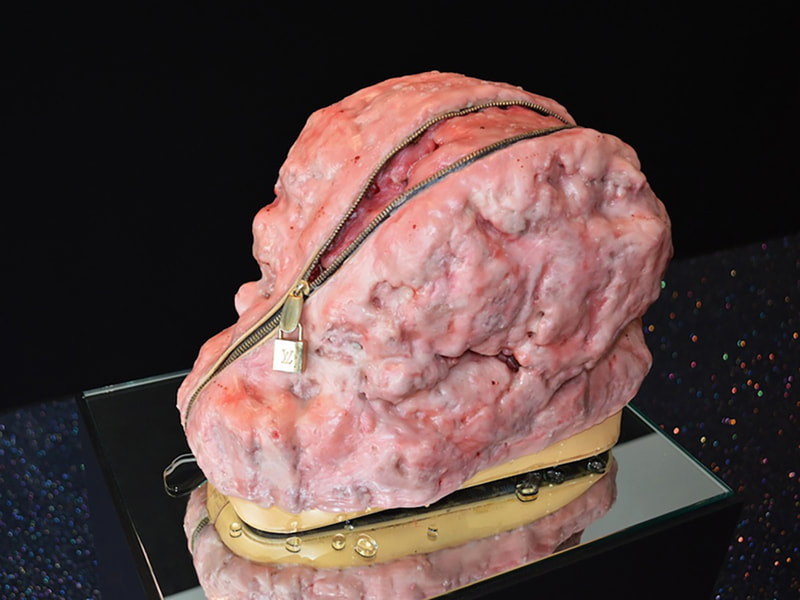

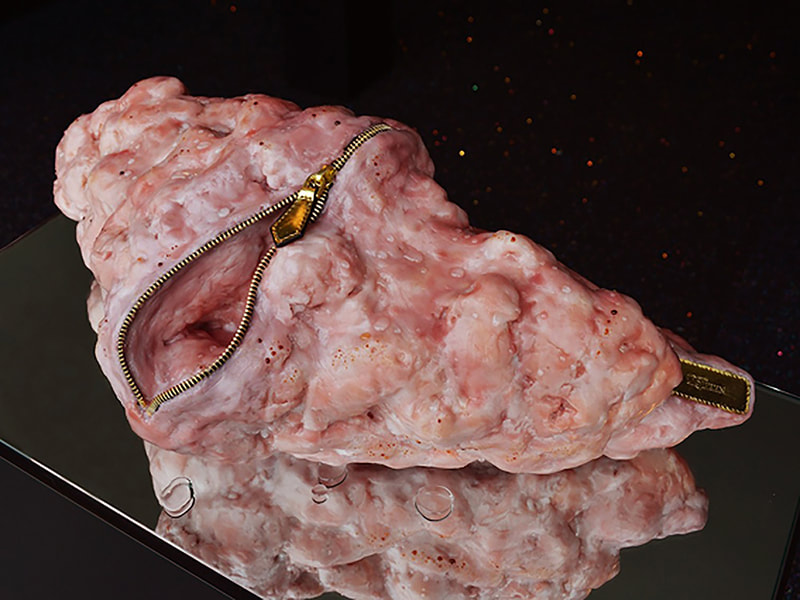

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU 'Andrea Hasler was born in 1975 in Zürich, Switzerland, and currently lives and works in London, UK. She holds an MA Fine Art from Chelsea College of Art & Design. Her wax and mixed media sculptures are characterized by a tension between attraction and repulsion. Her work depicts the emotional body, often working with skin as the physical element that divides the Self from the other, as well as the potential container for both and what happens if you open up those boundaries. Hasler’s work dissects moral ideas generated by the media and deeply entrenched concepts in our society without reassembling the dissected, separated and ornamented pieces into a new or different whole--thus confronts the viewer with his or her own feelings of attraction and repulsion. Solo projects include ‘Burdens of Excess’ Gusford Los Angeles/USA, Irreducible Complexity’ NextLevel-Projects, London/UK and ‚Full fat or semi-skinned?’ Bon Gallery, Stockholm/Sweden. Hasler won the 2014 Arts Council England funded Greenham Common Commission and created a large site specific installation which gained much press interest. Hasler chairs artist talks at Next Level-Projects, lectures at various institutions including the Sotheby's Institute of Art. In 2018, her work was include in the exhibition ‘Ethics, Excess and Extinction’ at El Paso Museum, Texas/USA. She was an ‘Artist-Resident’ at ‘Verbier 3D Foundation’, Verbier, Switzerland, where she created two sculptures for their Alpine Sculpture Park, she completed other artist-residency at Next Level Projects/Bahahmas and at Chisenhale, London/UK. In 2019, Andrea Hasler created a new body of work during her artist-residency at 'Verbier 3D Time + Space' in New York , which resulted in a solo show at 'Verbier 3D Foundation’s' new project space in Soho/New York City/US. Most recent projects include the group show 'Raum der Lusten' at Raum, Utrecht/NL together with Atelier van Lieshaut and Maarten Baas and 'Body-Works' a site specific installation with 'Wie wars mal mit' in Basel/Switzerland and Tagazout/Morocco in April 2022. Future projects include a site-specific installation in Marfa, Texas planned for Autumn 2023. Your art is marked by dichotomy—by the collaboration between enticement and disgust, luxury and grotesque. How did you develop your current style of wax sculptures? My practice centers around depictions of the emotional body—that which is not defined by the physical body but rather captures emotions—and I construct immersive installations and site-specific sculptures that are characterized by a tension between attraction and repulsion, something that can be aesthetically desirable yet revolting at the same time. Focusing on the psychological need to belong and emotional links to the “abject,” my work confronts viewers with their own corporeality. My interest lies in exploring the boundary between the Self and the “Other” (and how blurry that has become in our social-media-obsessed world), focusing on the skin as the physical element that segregates the two as well as the potential container for both. My work plays with visions of the future, scenes of surgical fetishes and glamor and unsettle the viewer with carefully staged and naturalistic wax reproductions of human organs in the form of luxury fetishes. The viewer is confronted with contradictions where desire and attraction are hovering back and forth to disgust and repulsion. A long-term subject in my work is the notion of our obsession with luxury, particularly luxury-travel in contrast to global migration. Why do we travel, what are we seeking, how do we portray this “Other”, and which “tribe” do we aspire to belong to? My work poses new questions in relation to the craze for luxury and status: How much can our bodies take? Will we sacrifice everything for beauty? What kind of person do you wish to be tomorrow? How much money will we spend to maintain our carefully curated and “filtered” version of ourselves? I honestly think that one day, it will not be the Rolex on your wrist that will be the ultimate luxury accessory, but kidneys embellished with diamonds. As soon as the exterior has been completely molded, plastic surgery of an internal organ is its logical consequence. This is the peak of the exclusive: The intervention is not visible--or only so on an x-ray! I live in a nomadic society, and I think the brands we choose are a reflection of the "tribe" we want to belong to. More importantly, they help us to become identified by other nomads, to become part of a group. This notion is driven by a sense of desperately wanting to belong that the philosopher Julia Kristeva links with our desire to recreate the symbiotic mother-infant relationship which stems from the consequent tragedy of the sense of loss when one realizes that they are an independent subject. So really, to put it simple: I think the craze for luxury is a longing for one’s nurturing mother. That’s such a fascinating way to think about the luxury craze. How did your interest in the body and luxury first develop? How did your art education play a role in supporting these interests? Growing up in Switzerland, famous for its understated take on everything, I was not prepared for the brashness and logo obsession in relation to luxury goods that I encountered when moving to London to study Fine Art. Long limited-edition waiting lists and queuing around the block for a pair of shoes were all new to me. So initially, my long-term project Burdens of Excess started by analyzing my own growing obsession with these items and by analyzing the emotional process of purchasing these goods. I became fascinated with the psychological aspect of consumerism, and its emotional link to “abject,” something that is aesthetically desirable, yet revolting: where the viewer’s attraction is replaced by repulsion. The accessories I deconstruct in Burdens of Excess are all items that I desire as a consumer myself. I lust after them for months and then I cut them up in the most cathartic way. My scarification of personal items started as an art student, as I simply didn’t have the budget to invest in new "material," so I would sit in my flat, look around and wonder what I could "sacrifice" next. The sacrifice element has by now turned into part of the process, the lusting and waiting for a particular fashion item, the excitement of purchasing and then deconstructing it, which I often document. My work is not at all a critique of the luxury industry, it’s an attempt to analyze the emotions behind it, starting with my own. In Burdens of Excess, I play with the aesthetic code of a chic, seductive luxury boutique setting with its black walls, glittery flooring and the way the organ objects are presented on plinths, hermetically sealed behind glass boxes. So in a paradox way, the deconstructed luxury items are back to where they belong. The subject matters of both the desire for luxury items as well as the darker side of plastic surgery’s intestine-liposuction filled accessories are both synonymous with what glamor/status represent for me—the desire to be accepted, to be part of the "tribe". Which brings us back to the "tribe" and the sense of so desperately wanting to belong. As certainties that used to shape the world around us are disappearing, I think hyperconsumerism has replaced religion in many ways. It gives people a sense of togetherness by displaying codes of where we ‘see’ ourselves associated with in an increasingly non-committal society that wants to leave all options open. Hyperconsumerism is fueled by brands, as we often form deep attachments to product brands, which affect people’s identity, and which pressure customers to buy and consume their goods. Another characteristic of hyperconsumerism is the constant pursuit of novelty, encouraging consumers to buy new and discard the old (no commitment required), particularly in fashion, where the product life cycle can be very short, sometimes just weeks. I believe that this endless cycle taps into an archaic feeling of emptiness with the hidden promise to gain a feeling of completeness with yet another purchase. It is built on selling an empty promise, that can not be fulfilled and only further fuels our desire for the next limited edition item in the hope that this will be the one that makes us feel at ease and secure in a world where many know certainties have split apart and become blurred lines. As I mentioned in the earlier question, in psychoanalysis, this triggered feeling relates to a child’s first painful realization that they are not part of a symbiotic cycle with their mother, the realization of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’. Julia Kristeva and I believe hyperconsumerism can be traced to fueling exactly this feeling, which I find incredibly fascinating. I love your piece “Matriarch.” The symbolism is exceptional. Is your process for creating work when you’re commissioned different than when you create on your own? My research and working process is very different when working on a commission as there are the parameters set by the brief that comes with it, whereas working on my own projects is much freer. That being said, I do like the challenge of the “restrictions” that can come with a commission and ways to work around it and find solutions that fit with my process. “Embrace the Base” was a Arts Council England-funded commission to create a new body of work for Greenham Common. Greenham Common is a former American army base in the United Kingdom and “The Matriarch” was one of the sculptures that I created for it. ‘Embrace the Base’ takes the Greenham Common’s history as a starting point, particularly the Women’s Peace Camp that has been situated there for almost 20 years to protest nuclear weapons stored on site. This was the longest peaceful women’s protest in history and they succeeded—in the end, the site got decommissioned to store nuclear weapons! One of the banners at the time had the slogan “Embrace the Base” which became the title of my installation. For this commission, I took a political element as the starting point and related it back to body politics. Metaphorically I took the notion of the tents, which were on site during the Women’s Peace Camp, as the container for emotions and “humanized” these elements to create emotional surfaces: the nylon tents fabric are used as a metaphor for skin, as the containers to project emotions. The women’s protest was driven by the fearful impact the nuclear threat would have on them and on their children. The large igloo tent, “The Matriarch” represents the place where this fear manifests itself. In the core of the female body, the womb and “Next of Kin” symbolizes its child counterpart. The three intestine figures explore the notion of a nuclear aftermath. One of the large American culture websites featured this work and described it as ‘meat’, which resulted in hundreds of people leaving comments mourning dead animals, when in fact the flesh-like appearance is made from wax! I take it as a compliment for my practice that people mistake it for something else. “The Matriarch” was installed on the actual site at Greenham Common where the protesters' tents were pitched years before. This particular sculpture marked the beginning of an important shift in my work towards site-specific outdoors installation or interventions. It extended my way of creating artwork beyond classic gallery spaces in mind and made me reassess the way we exhibit art in surroundings we don’t expect, and how different people engage with it. This project formed the basis of an extensive research of specific locations that challenge, interpret, and inform my work. This new way of working integrated a fresh direction of my own identity and creativity into my work and opened up communications and collaborations with other artists and organizations, which continues to shape and inform my work . The project that closely followed “Embrace the Base” was “Perishable Goods,” which was installed on the mountain above the Swiss Alpine resort of Verbier at the Alpine Sculpture Park of the Verbier 3D Foundation. “Perishable Goods” is a pallet of compressed flesh (again made from wood/wax/resin) bulging out, yet held together and at the same time, and adorned with luxury chains. With the impression of the work being crudely dropped on top of the mountain, installed for 5 years, the work suggests the intensity and intrusion of the change of population in Verbier in the winter months whilst referencing the stark contrast of the need for emergency aid food pallets dropped off in disaster zones. The sculpture slowly decayed over the period it was installed, like meat: The top fleshy wax layer melted away with the sun and revealed the underneath, more fleshy intestine layer which is resin and the gold chains started to rust. The photographs of your sculptures on the Swiss Mountains and Moroccan Sahara Desert evoke brilliant juxtaposition. How do you decide which sites are suitable for your artwork to inhabit? It’s a mixture of sourcing locations that fascinate me and liaising with arts organizations that could be interested in the project. For example, with ‘Perishable Goods Verbier’, I was invited to do an artist residency by the Verbier 3D Foundation. As part of my residency, I spent 6 weeks in the mountain resort of Verbier/Switzerland and one thing that struck me was that in the off-season, 4000 people are living there and in the winter season, the population increases to 40,000 people. I started to think about this number of luxury tourists…like they were compressed flesh which then resulted in creating "Perishable Goods" on site. During my time in Verbier, I also created another sculpture called "Avant/Aprés" which consists of a red carpet scenario in the mountain landscape with no indication which boundary is the VIP side to aspire to be or which one we may be held back from. The work touches on the seclusion, exclusivity, and hybridity of the mountain town of Verbier, famous for attracting luxury tourists. In relation to the "Mutation" theme of the artist residency; the work points at the lack of actual physical mutation and the desire to be different or transform. The intestine-like rope made of resin and wax, references the non-physical aspect of desire, highlighting the fact that underneath we are all the same. As I was looking for suitable locations to install the work, the idea for a video-installation developed and I filmed a video-piece depicting bizarre imagery of an unsuitably dressed luxury tourist in an evening dress and high heels walking around the Swiss mountain endlessly searching for the VIP area atop a Swiss mountain, lugging gold poles, a red carpet and an "intestine" rope. The video-installation Avant/Aprés embodies the desire to belong and aspirations of VIP-ness - the endless search for inclusion, climbing to reach the peak and the accompanying sense of exhaustion. The piece manifests the fundamental psychological need to belong, and the constructed culture of the exclusiveness of the ‘VIP’ which goes back to wanting to belong to a ‘tribe’, in this instance a very exclusive one. I developed the idea for “Perishable Goods No.5” two years later. In this instance, I sourced the desert location myself as I was looking for a site that stood in total juxtaposition to the Swiss Mountains. I worked with Next Level Projects, an arts organization here in the UK, to help with the logistics of installing the work in the Erg Chebbi desert in Morocco. Of course, with the desert heat, the wax melted away much quicker than its counterpart in Switzerland. Both locations are in stark contrast to each other, and both represented different challenges, but I was equally happy with how the work inhabits either of the two locations and how the surroundings inform its meaning differently. All art, especially yours, elicits some sort of response from viewers. What is your relationship to how your artwork is received, especially when you rely on the emotions of disgust and appeal? Is it the artist’s responsibility to care how their work is received?

Of course, I want people to engage with the work but I have no desire to have control over how people respond to the work and it is very interesting for me to witness people’s reactions. The reactions vary greatly—there are people who can’t look at these objects or feel nauseous. It’s fascinating how people are often repulsed by the abject quality of a sculpture, but also at the same time really want to touch it. It is that grey zone where desire and repulsion hover back and forth that I’m attempting to capture with my work. You’ve also created gold medical instruments that are all distorted in some way. What was the inspiration behind them? Do you see yourself working in materials other than wax? The gold medical instruments series work with the notion of the foreign intrusive pain-inducing object that becomes the body itself as it blurs the lines between inside/outside of the body and Self & Other. I particularly looked at medical instruments that are used during childbirth and how to “emotionalize” these cold, stark metal objects in contrast to the soft fluid body they invade, such as forceps that were first developed in the 1600s and where the design remains largely the same. I gold dipped these sculptures to play on the notion of desire and luxury, so for example ‘The Bvlgari Edition Forceps’ are adorned with diamantes and a tiny little luxury brand logo. Sometimes wax isn’t suitable for a specific commission, so I now often work with resin and incorporate less wax, or just an outer layer of wax. Saying that, wax is still my favorite material to sculpt with—it allows for flexibility and there is never an endpoint, so a piece can “rest” for months before I warm it up to work on it again. Years later, I still enjoy the ritual element of melting wax: the slow process, building up layer after layer. INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Noor Hindi (she/her/hers) is a Palestinian-American poet and reporter. Her book, Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow is out with Haymarket Books. She is a 2021 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellow. Follow her on Twitter @MyNrhindi. Hi Noor! Congrats on Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow.! It’s so propulsive and unflinching. I pause at lines and wow. I want start by asking you about “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying” which so well-deservingly blew up last year. What was your reaction to the attention the piece received?

First of all, thank you so much for reading the collection and spending time with the poems. I think the biggest motivator for me in writing the book was seeking community and connection. I felt so connected to the authors of the collections that I read when I was studying and exploring poetry, so I'm really glad to hear that the book resonated with you so much. “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying” was a wild experience. I didn't expect the poem to blow up the way it did. But I think because of the pandemic, the George Floyd protests, and Israel threatening to and evicting families living in Sheikh Jarrah, there was a lot of anger and tiredness in our country and worldwide and the poem resonated with many people. And the coolest thing was just to be able to reach so many people and respond to them and say thank you and hear about their personal reading of it and how it connected to them. You end ““Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying” with the line “One day, I’ll write about the flowers like we own them.” Those words are shattering. They’re especially shattering because that day may never come, or when it does, we’ll be long gone. How do you assess poetry's capability as activism and advocacy when so much feels out of our control? A protest poem is not a protest. It's not a burning of a police building. It's not a change of legislation. But what poetry does is give voice to the people who are most impacted by violence, by colonialism, by climate disaster. For example, rather than somebody reporting on an event that impacts people, a poet is able to just write their own story, document their own history, and be a voice that connects to other people like them. For me, emerging into the literary scene reading queer Palestinian and Arab poets, I knew that I wasn't the only one and felt less lonely and alienated. I hope that by writing my own poems, I’m reaching audiences that need to be reached to empower them. There’s humor blended into the poems in Dear God. Dear Bones. Dear Yellow. I loved the lines “I assimilated so much / I drink Diet Coke / at the rate of a middle-aged / white woman” in “Broken Light Bulb Flickering Away” and the sarcasm in “Self Portrait as Arab/Muslim Teenager in an All-White High School.” But I felt something bitter about the humor—it becomes a coping mechanism against the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy, against America. Can you speak more about the humor in the book? I really believe in humor's ability to access hurt and make a point without feeling too heavy. It’s a useful mechanism. People don't expect when you're writing about immigration, sexuality or sexual violence, for there to be an element of humor. But I think in our human existence, there are varying emotions and ways of coping that I often don't see represented in poems that are tackling these tougher subjects. Personally, I think entering the poems with a certain level of light-heartedness allows me to access my own voice to be able to talk about difficult topics without coming to the page with this sense of heaviness and dread. Another topic you navigate is your difficult relationship with journalism. Does observing the violence, voyeurism, and dehumanization of journalism prompt you to approach your journalism differently? I was on this crusade for years when I was doing journalism to convert more reporters to poets, and or at least get them to read poetry. Because so often reporters are interviewing subjects—people who are experiencing violence or racism—but we are still the gatekeepers of their voice. We’re choosing which quotes to pick. Sometimes we're using their narrative, their story, and their voice to explain a larger phenomena. Poetry, on the other hand, is a person’s unfiltered voice and experience. It’s documentary. Solmaz Sharif’s work, for example, incorporates family, history, and photography. Poetry is so empathetic and attuned to the heart, but reporting doesn't always feel that way. In reporting, there's a structure and an argument that’s presented through statistics or a study. I think it's worth reading a person's perspective for the sake of reading it and experiencing that story first-hand and sitting with their art. I also think that poetry taught me to be in touch with feelings and sit through the pain. When you're reporting, you're not always able, or you don't have the time to process everything that you're seeing, which ultimately does a disservice to what you publish. Despite your critique of journalism, you still pursue journalism. Can you describe that dissonance? I actually published my last story in August of 2021, so we're nearing roughly a year since I’ve stopped reporting. I’m working in communications and marketing now and I haven't returned to reporting. I burnt out. But it's something that I continue to use in my poetry. What journalism taught me is how to connect to communities, how to find information, and how to interact with documents. I still use the skills even though I'm not currently practicing it. Many of the poems Dear God, Dear Bones, Dear Yellow respond to or incorporate journalism. The use of headlines in “Good Muslims Are All Around Us” is so powerful. How does your work in poetry and journalism overlap and carry over to one another? As a child growing up in the United States, and as somebody who was six years old during 9/11, growing up in the supercharged anti-Muslim rhetoric, it's always been fascinating to me the ways in which headlines report articles and how the language that we use creates violence that can be targeted to a specific group of people consciously or not consciously. When somebody hasn't taken the time to think about language and its impact, there are implications to the words they put on a page. I was very aware of the consequences of reporting. Reports about Palestine, for example, often say Palestinian children have been shot dead by Israeli officers. They’re referred to as shot dead and not murdered, which implies that there isn't this connection between the perpetrator and the victim. You also see this a lot with the way that we talk about the killing of Black men in this country by police officers in the use of the active versus passive voice. Growing up in that atmosphere taught me to be more critical. One of the most poignant moments in the book is the USCIS Trip poems, where you detail your grandmother’s relentless and excruciating journey to become an American citizen. How do you go about having conversations with people who hold such contrasting, and often heavily idealized, images of America? America often creates wars, meddles into other countries. create chaos, and wreaks havoc on generations. Then we become refugees or have a need to immigrate to this country as a direct result of America being a colonial nation and American interests always being put above all else in the world. When you are somebody who is white and or has grown up in this country and hasn't been to other countries, you believe that the world revolves around the United States, that it is the center of the universe. With my grandma, she was happy to receive her citizenship and felt a sense of safety and stability in having her citizenship. But I continually ask: at what cost? I ask that question with the knowledge that it's a question I'm asking from a place of privilege as somebody who did not grow up in Palestine. I was born in Amman, Jordan and I didn't grow up there either, so there's a lot that I didn't experience. There is still this image of America being the land of opportunity. In a lot of ways, some of the poorest people in this country are perhaps richer than people in other countries around the world. We know this to be true in some ways, but I just continually question the consequences. I’m wondering with relatives, like your grandmother, who still blissfully believe in America, are these conversations even worth happening? Family and politics are really difficult to navigate. It's really hard for me to come to her and tell her to be critical of this country when she is limited in the amount of water that she can use every week in Amman. She’s limited in the amount of gas she can use and parts of her home are not heated in the winter. For me to come and tell her to be critical of America, as I'm sitting in an air conditioned and heated home, and have this ability to use as much water as I please, is a privilege. I haven't navigated that conversation. And I, throughout the process of her receiving her citizenship, helped her with it. I wasn’t going to break her bubble of joy with whatever criticism I had. She deserves to be happy. In “I Buried My Father Last Winter,” you write “The first time I met my father, I was interviewing a Bhutanese refugee.” When I spoke to Diana Khoi Nguyen, she discussed that she spoke with members of the Vietnamese diaspora due to the silence sustained by her parents. Do you share a similar experience? My dad was somewhat open about talking about his experiences. I was working on a story at the time for a magazine about a community that was living in Akron, Ohio, which is where I grew up. The community consisted of predominantly Bhutanese and Nepali refugees. I was fascinated by their experience of coming to this country because it mirrored my grandparents’ experience of having to navigate language barriers and watching this generational divide with their kids. In the poem, I quoted the words from a refugee I interviewed. It mimicked a lot of what my parents often said to us or accused us of growing up because of the strangeness and distance we felt from not growing up in the same place, not speaking the same language, and not having an affinity for the same food. White people, for example, often go to the same high school as their parents, or share similar experiences, and I think there’s a closeness and intimacy in that. But children of immigrants don't experience that. When I was interviewing this refugee, I was at this place of empathy and understood the sense of betrayal and loneliness with one’s children and new country. You open with an epigraph “Let this book be an invitation, as prayer, as love.” Moments of love are dispersed through the book. In “USCIS Trip #2,” you write “I want my rage to elicit love and more love. I want people to stop asking if I love this country.” In the last piece, “Pledging Allegiance,” you question, “What does it mean to love? A country? A book? A people?” How do you intend the book to serve as love? What does it mean to proffer this book as love when you question its definition? In a way, I wrote the book from a place of isolation and loneliness and a desire to connect. My sense of safety, community and belonging and feeling loved came from reading other writers like Tarfia Faizullah, Randa Jarrar. Safia Elhillo, and Kaveh Akbar. All of these people made a huge impact not only on my work, but also on my mental health and ability to navigate the world. I see the book as an act of love and vulnerability. I think that often your first book as a poet tends to be autobiographical because you have all these experiences you’re going through. I wanted that first page to welcome people in and to make them feel safe and to establish a connection. INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Jireh (they/them) is a queer Taiwanese/Hong Konger American poet and multimedia journalist born and raised in the San Gabriel Valley. Their poetry and prose appear in The Rumpus, Asian American Writers’ Workshop, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and more. As an artist, they’ve collaborated with filmmakers at Level Ground and the Human Rights Campaign to bring their poetry to screens. They are a screenwriter in training with Get Lit, Words Ignite and a current documentary fellow with the Asian American Journalist Association Voices program. As an intern, they worked at The Los Angeles Times and NPR. Most recently they were an associate producer with CapRadio on a new podcast “Mid Pacific” on Asian American identity. They volunteer as the student representative for the Los Angeles chapter of the Asian American Journalist Association. You can follow their work on Instagram and Twitter at @bokchoy_baobei or at jirehdeng.com. One of my favorite poems of yours is “Where I prove by induction, humanity,” where you so brilliantly incorporate math. I loved how you mapped out a math problem and presented scratchwork at the bottom. How did you navigate the collaboration between poetry and mathematics?

I was inspired by taking a proof-based math class. I was a math major for two years and actually only needed to take one more class to be a math minor, but I’m done with school and don’t want to think about it anymore. Although I am no longer taking math classes, math still affects how I think. I was thinking, what if I wrote a poem as a math proof? I was also taking a class with this professor who was insightful about not only math, but also the humanities. She explained many concepts in an interesting way and encouraged us to include our scratch work on the side. What was uncomfortable about the proof-based math class was the ambiguity because I was always wondering if I was answering the problems correctly. I was struggling a lot because I’m better at plugging in numbers and working with very concrete rules. There’s a certain math logic, which is why math majors actually score very high on the LSAT. This class opened up space for me to think about how poetry is structured and how the world works at a macro and micro level. I’m also really fascinated by your poem “Thanks, but the role of white girl is already taken,” where it’s first a contrapuntal and then you employ erasure on the initial poem to create a new understanding. Can you walk me through the development of this poem? For the first eighteen years of my life, I lived in the San Gabriel Valley, which is mostly Asian American and Latinx. Going to college was a culture shock because I went from being one of many Asian Americans in a room to suddenly being the only Asian American. During the pandemic, many white women were making my life very difficult in a myriad of ways because they were racist. I was shocked by the audacity because growing up, I didn’t experience white people acting like they owned things, owned time, or owned a space they walked into. The Asian American culture I grew up in, especially my church community, had an emphasis on being deferential, polite, and going out of your way to be considerate towards other people. When I moved out during the pandemic, I had a racist roommate and I was shocked by her audacity to say such racist things. It was compounded by the fact that I was working at my student newspaper at the time, which was really problematic. I was constantly being gaslit by the white women that were in that journalism program. I remember countless frankly ridiculous things people told me that almost made me quit journalism. Someone, who I considered to be a mentor at that time, said I was too focused on racism and that I was distracted from getting the right work done. That’s true in some regards. There’s a quote from Toni Morrison where she says “racism is a distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being.” As a person of color, you have to constantly prove that you’re human before people read or consider your work seriously. I think this not only applies to journalism, but also to poetry and any type of literature. You’re a hyphenated American. The white woman who was ignoring what I was saying about racism was essentially saying I was the distraction. When my poem, “Thanks, but the role of white girl is already taken,” was first published, I was worried that someone might find it and nail me on the cross for my journalism because in journalism, you’re required to remain unbiased. I don’t think I ever have had the choice to be unbiased. Especially as a queer Asian American, my identity is always up for debate. My humanity is up for debate. This poem really came from a place of frustration. I realized that whiteness isn’t about the color of your skin, it’s also about the way you behave in the world. That’s why people of color also act like white people and in structures of whiteness. What shocks me about American culture is how individualistic and how selfish many people are because everyone is trying to make it for themselves and as a result don’t show up for one another. A piece of unsolicited advice is to please never take a workshop if it’s not led by an anti-racist. During workshops, I’ve felt that my work was put into a category of “other'' and I’ve been told my work is too specific and not relevant to the white gaze. In the second part of the poem, which is erasure, I thought of it not as a blacking out, but as a disappearance. I grew up in a bilingual household but then lost the ability to speak Chinese. I felt the loss of language. Instead of a word being covered up, words simply did not exist for me. Erasure through the blank page, rather than erasure through blackening out lines, feels more appropriate to how I've been experiencing language throughout my entire life. I almost think that words are almost like dust particles, floating around in the second half of the poem. Thank you for sharing that and thank you for your advice. You venture into many different art and writing mediums—poetry, prose, journalism, photography, mixed media—that it’s impossible to define you into a singular craft. What does being an artist mean to you? How does each artistic field you pursue interact with one another? Poetry was the way I entered the art and writing world and I’ve always been interested in the intersection of poetry and journalism. I’m deeply afraid that I won't get to tell the stories that I want to tell. Life is short and I want to make things that outlast me. As an artist, my mission is to always humanize. I’m very disinterested in representation politics, which is thinking appointing a queer person or person of color as the head of an organization will magically cure 200 years of racism and homophobia. If racism and homophobia existed for 200 years, it’s going to take another 200, if not more, years to truly fix it. My work is an extension of my identity. The main thing I want to move into is directing and producing films now. I always loved visual stories and I want to take an active part in storytelling. Film and journalism are very much about the act of witnessing. Right now, I want to move away from realism and more into fictional work. But it’s very difficult to be a filmmaker without having gone to film school. I’ve never taken a single class in film or documentary. I’ve had to learn things along the way and teach myself how to use different software. How do you balance creating multiple types of art and writing, especially while also attending school? Honestly, it was very hard. I spent a whole year working full time while also being in school full time. This summer, I was supposed to go to Kansas to work full time, but I didn’t because I was burnt out. I’m also broke because I decided I needed to be financially independent from my parents for mental health reasons. I don’t hold anything against my parents, but sometimes it takes them five years to figure out things it takes the rest of us five seconds to because they’re from a different generation. I’m not excusing how they’ve behaved, but for my personal safety, I had to move out. But I’ve never taken a job that doesn’t move me emotionally or doesn’t align with my beliefs. I wake up every morning excited to be doing what I’m doing. I was depressed and suicidal as a kid. The loneliness of queer youth was very difficult and compounded by the fact that I’m Asian. When your family doesn’t talk about where they came from, your history is obliterated. At the same time, your future is obliterated because your parents are unsupportive. My parents are deeply religious and were concerned that I was going to hell. Now, being grounded in a community where I am able to produce beautiful art and storytelling feels so revolutionary. The world feels more infinite and boundless. I feel so lucky now that I’m doing what I dreamed about two, three years ago. I have this sense of urgency to be working out of financial need but also out of the desire to be closer to people because the nature of being a journalist and storyteller is to be close to people. You wrote in The Washington Post “learning to protect myself is also a political act of defiance: I refuse to play the role of a victim, or to rely on the police for my personal safety.” Does pursuing art and writing create the same defiance for you? Yes. I've never felt like there was a moment where I had to look to an institution to give me validation for my artwork. Art to me is a living, breaking thing that interacts with people in open and mysterious ways. I have such fondness for the local art galleries and museums that are embedded in neighborhoods. I’m also proud to have a nexus of connections in the art world. I can point people who have connected me to others to other folks. There's something very serendipitous about that. Connections are made because genuinely, we want to see each other all succeed. Of course there are barriers in the art world, but I’ve never felt that people haven’t been rooting me on. As a journalist, my job is to always be like a cultural frontline worker who is always recording history. I want to recognize spaces that have historically been lost. If you don’t write about a topic or event, it’s almost like it never existed. So much of my family history has been obliterated because we don’t know or talk about it. My obsession as a journalist is to record history so that it doesn’t get lost. As a queer person, the future feels ambiguous, which is why I’m very rooted in the documentation aspect of my work. Sometimes I wish that I could write about anything and not care about reality at all. I was reading K-Ming Chang’s Gods of Want and I thought it was so badass how she can just write about the fantastical and the craziest inventive things. I struggle to make up lies, so maybe that’s why my work is so grounded in reality. I want to tell real stories and capture people’s experiences so that I can incorporate them into my work. K-Ming Chang is a visionary. Another poet and journalist I really love is Noor Hindi, who wrote in “Breaking [News]” that “Reporting is an act of violence–poetry one of warmth.” Do you feel similarly about the difference between creative writing and journalism? Yes, I know Noor! Noor’s a beast when it comes to the page. She’s such a powerful poet. I'm always grappling with power dynamics as a journalist. There’s an inherent extractive nature of journalism, in which you’re entering a community, taking a story, and leaving them behind. That really bothers me about the profession and why I don’t conduct myself in a typical journalist way that is distant and separate. Journalists can’t be robots and always objective. We’re real, living humans and we interact and shape the world. The way that we see the world informs how others see the world. It is inherently violent because journalism historically hasn’t been inclusive. Look at who’s owned large newspapers, whose perspective is being told, who has power over how the media is told. There are a lot of journalists with that urgency to be fair and accurate, but there are a lot of us that don’t have the understanding of what it’s like to live in precarity, in the margins. I grew up in a middle-class community and had privileges like food security, but my family did not have an excess of money and were very frugal. My parents did not think I could make a career as a writer. The fact of the matter is that in journalism, it’s very difficult for low-income people to break in because it’s so hard to get an internship and most are unpaid. Being a journalist can also be violent towards yourself. I purposely try to stay away from trauma-porn-type stories. Instead, I’m invested in stories of queer joy. The representation we need is not of queer people dying and suffering–I know that exists–but I don’t want to be defined by constant suffering. I’m not a victim, I’m powerful. As an artist, I believe the future is now. We have the choice today to decide how we want to be liberated in the future. Joy is resistance. Noor and I have talked about how it’s difficult to balance poetry and journalism. But I constantly turn to both. When journalism is breaking my heart, I turn to poetry. And when poetry can’t reveal what I want it to, I turn to journalism. Although they’re different fields, both of them do the same work of recording history and telling stories, which I want to do. As a young writer, have you felt overwhelmed or pressured to write a certain way by the professional literary scene? No, but I do feel a lot of pressure to be financially stable while doing something I'm passionate about. Certain jobs would really crush my soul, such as reporting on breaking news. Breaking news is another way journalism is inherently violent—you’re not sitting with the stories, you're turning them out. Breaking news is often reported in a way that dehumanizes its subjects without context and without care for the person(s) harmed and their community. Asian American Pacific Islander hate crimes have been reported very problematically because they tend to pit Black perpetrators against the Asian American community without contextualizing and people assume an easy narrative. These narratives are not neutral but shape our realities and how we treat people. Anything else you’d like to share? Being an artist is hard and exhausting, but I believe I have the endurance to keep doing projects to completion. And I will bring other people along with me because it's never a solo race. The beautiful part of growing as an artist is realizing that so many of us are on similar journeys and so many of us want to support one another. It’s my goal to amplify my peers and make the most noise possible. |

Archives

April 2023

Artists

All

|