|

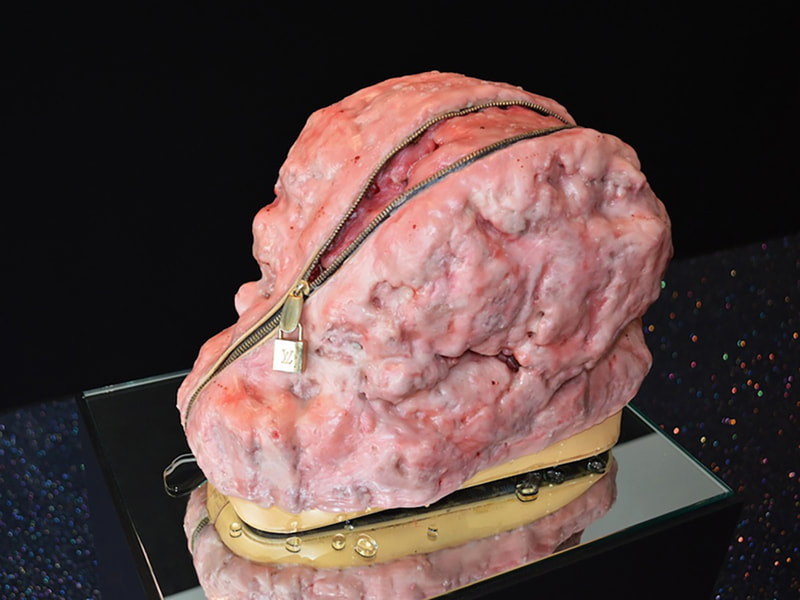

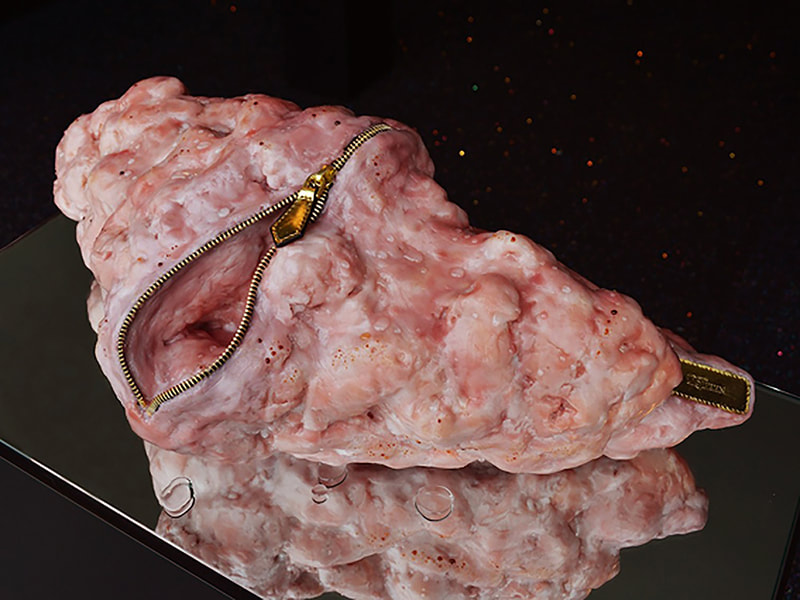

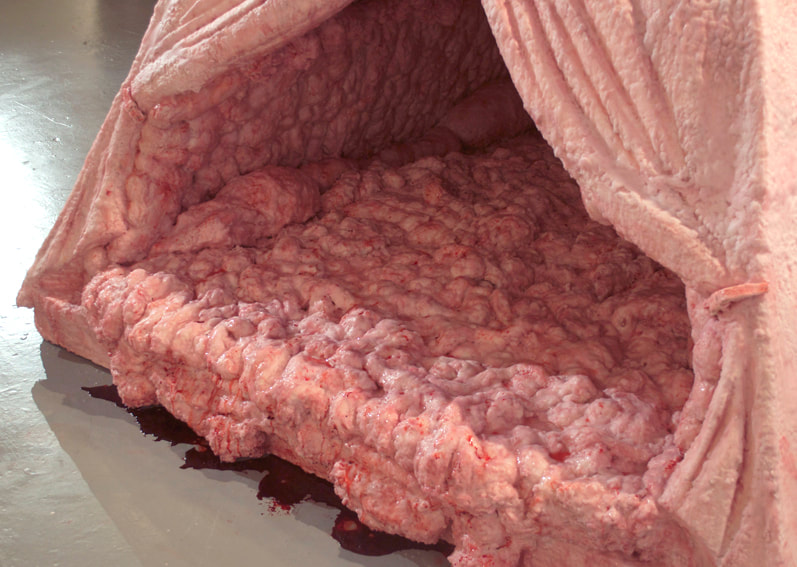

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU 'Andrea Hasler was born in 1975 in Zürich, Switzerland, and currently lives and works in London, UK. She holds an MA Fine Art from Chelsea College of Art & Design. Her wax and mixed media sculptures are characterized by a tension between attraction and repulsion. Her work depicts the emotional body, often working with skin as the physical element that divides the Self from the other, as well as the potential container for both and what happens if you open up those boundaries. Hasler’s work dissects moral ideas generated by the media and deeply entrenched concepts in our society without reassembling the dissected, separated and ornamented pieces into a new or different whole--thus confronts the viewer with his or her own feelings of attraction and repulsion. Solo projects include ‘Burdens of Excess’ Gusford Los Angeles/USA, Irreducible Complexity’ NextLevel-Projects, London/UK and ‚Full fat or semi-skinned?’ Bon Gallery, Stockholm/Sweden. Hasler won the 2014 Arts Council England funded Greenham Common Commission and created a large site specific installation which gained much press interest. Hasler chairs artist talks at Next Level-Projects, lectures at various institutions including the Sotheby's Institute of Art. In 2018, her work was include in the exhibition ‘Ethics, Excess and Extinction’ at El Paso Museum, Texas/USA. She was an ‘Artist-Resident’ at ‘Verbier 3D Foundation’, Verbier, Switzerland, where she created two sculptures for their Alpine Sculpture Park, she completed other artist-residency at Next Level Projects/Bahahmas and at Chisenhale, London/UK. In 2019, Andrea Hasler created a new body of work during her artist-residency at 'Verbier 3D Time + Space' in New York , which resulted in a solo show at 'Verbier 3D Foundation’s' new project space in Soho/New York City/US. Most recent projects include the group show 'Raum der Lusten' at Raum, Utrecht/NL together with Atelier van Lieshaut and Maarten Baas and 'Body-Works' a site specific installation with 'Wie wars mal mit' in Basel/Switzerland and Tagazout/Morocco in April 2022. Future projects include a site-specific installation in Marfa, Texas planned for Autumn 2023. Your art is marked by dichotomy—by the collaboration between enticement and disgust, luxury and grotesque. How did you develop your current style of wax sculptures? My practice centers around depictions of the emotional body—that which is not defined by the physical body but rather captures emotions—and I construct immersive installations and site-specific sculptures that are characterized by a tension between attraction and repulsion, something that can be aesthetically desirable yet revolting at the same time. Focusing on the psychological need to belong and emotional links to the “abject,” my work confronts viewers with their own corporeality. My interest lies in exploring the boundary between the Self and the “Other” (and how blurry that has become in our social-media-obsessed world), focusing on the skin as the physical element that segregates the two as well as the potential container for both. My work plays with visions of the future, scenes of surgical fetishes and glamor and unsettle the viewer with carefully staged and naturalistic wax reproductions of human organs in the form of luxury fetishes. The viewer is confronted with contradictions where desire and attraction are hovering back and forth to disgust and repulsion. A long-term subject in my work is the notion of our obsession with luxury, particularly luxury-travel in contrast to global migration. Why do we travel, what are we seeking, how do we portray this “Other”, and which “tribe” do we aspire to belong to? My work poses new questions in relation to the craze for luxury and status: How much can our bodies take? Will we sacrifice everything for beauty? What kind of person do you wish to be tomorrow? How much money will we spend to maintain our carefully curated and “filtered” version of ourselves? I honestly think that one day, it will not be the Rolex on your wrist that will be the ultimate luxury accessory, but kidneys embellished with diamonds. As soon as the exterior has been completely molded, plastic surgery of an internal organ is its logical consequence. This is the peak of the exclusive: The intervention is not visible--or only so on an x-ray! I live in a nomadic society, and I think the brands we choose are a reflection of the "tribe" we want to belong to. More importantly, they help us to become identified by other nomads, to become part of a group. This notion is driven by a sense of desperately wanting to belong that the philosopher Julia Kristeva links with our desire to recreate the symbiotic mother-infant relationship which stems from the consequent tragedy of the sense of loss when one realizes that they are an independent subject. So really, to put it simple: I think the craze for luxury is a longing for one’s nurturing mother. That’s such a fascinating way to think about the luxury craze. How did your interest in the body and luxury first develop? How did your art education play a role in supporting these interests? Growing up in Switzerland, famous for its understated take on everything, I was not prepared for the brashness and logo obsession in relation to luxury goods that I encountered when moving to London to study Fine Art. Long limited-edition waiting lists and queuing around the block for a pair of shoes were all new to me. So initially, my long-term project Burdens of Excess started by analyzing my own growing obsession with these items and by analyzing the emotional process of purchasing these goods. I became fascinated with the psychological aspect of consumerism, and its emotional link to “abject,” something that is aesthetically desirable, yet revolting: where the viewer’s attraction is replaced by repulsion. The accessories I deconstruct in Burdens of Excess are all items that I desire as a consumer myself. I lust after them for months and then I cut them up in the most cathartic way. My scarification of personal items started as an art student, as I simply didn’t have the budget to invest in new "material," so I would sit in my flat, look around and wonder what I could "sacrifice" next. The sacrifice element has by now turned into part of the process, the lusting and waiting for a particular fashion item, the excitement of purchasing and then deconstructing it, which I often document. My work is not at all a critique of the luxury industry, it’s an attempt to analyze the emotions behind it, starting with my own. In Burdens of Excess, I play with the aesthetic code of a chic, seductive luxury boutique setting with its black walls, glittery flooring and the way the organ objects are presented on plinths, hermetically sealed behind glass boxes. So in a paradox way, the deconstructed luxury items are back to where they belong. The subject matters of both the desire for luxury items as well as the darker side of plastic surgery’s intestine-liposuction filled accessories are both synonymous with what glamor/status represent for me—the desire to be accepted, to be part of the "tribe". Which brings us back to the "tribe" and the sense of so desperately wanting to belong. As certainties that used to shape the world around us are disappearing, I think hyperconsumerism has replaced religion in many ways. It gives people a sense of togetherness by displaying codes of where we ‘see’ ourselves associated with in an increasingly non-committal society that wants to leave all options open. Hyperconsumerism is fueled by brands, as we often form deep attachments to product brands, which affect people’s identity, and which pressure customers to buy and consume their goods. Another characteristic of hyperconsumerism is the constant pursuit of novelty, encouraging consumers to buy new and discard the old (no commitment required), particularly in fashion, where the product life cycle can be very short, sometimes just weeks. I believe that this endless cycle taps into an archaic feeling of emptiness with the hidden promise to gain a feeling of completeness with yet another purchase. It is built on selling an empty promise, that can not be fulfilled and only further fuels our desire for the next limited edition item in the hope that this will be the one that makes us feel at ease and secure in a world where many know certainties have split apart and become blurred lines. As I mentioned in the earlier question, in psychoanalysis, this triggered feeling relates to a child’s first painful realization that they are not part of a symbiotic cycle with their mother, the realization of ‘Self’ and ‘Other’. Julia Kristeva and I believe hyperconsumerism can be traced to fueling exactly this feeling, which I find incredibly fascinating. I love your piece “Matriarch.” The symbolism is exceptional. Is your process for creating work when you’re commissioned different than when you create on your own? My research and working process is very different when working on a commission as there are the parameters set by the brief that comes with it, whereas working on my own projects is much freer. That being said, I do like the challenge of the “restrictions” that can come with a commission and ways to work around it and find solutions that fit with my process. “Embrace the Base” was a Arts Council England-funded commission to create a new body of work for Greenham Common. Greenham Common is a former American army base in the United Kingdom and “The Matriarch” was one of the sculptures that I created for it. ‘Embrace the Base’ takes the Greenham Common’s history as a starting point, particularly the Women’s Peace Camp that has been situated there for almost 20 years to protest nuclear weapons stored on site. This was the longest peaceful women’s protest in history and they succeeded—in the end, the site got decommissioned to store nuclear weapons! One of the banners at the time had the slogan “Embrace the Base” which became the title of my installation. For this commission, I took a political element as the starting point and related it back to body politics. Metaphorically I took the notion of the tents, which were on site during the Women’s Peace Camp, as the container for emotions and “humanized” these elements to create emotional surfaces: the nylon tents fabric are used as a metaphor for skin, as the containers to project emotions. The women’s protest was driven by the fearful impact the nuclear threat would have on them and on their children. The large igloo tent, “The Matriarch” represents the place where this fear manifests itself. In the core of the female body, the womb and “Next of Kin” symbolizes its child counterpart. The three intestine figures explore the notion of a nuclear aftermath. One of the large American culture websites featured this work and described it as ‘meat’, which resulted in hundreds of people leaving comments mourning dead animals, when in fact the flesh-like appearance is made from wax! I take it as a compliment for my practice that people mistake it for something else. “The Matriarch” was installed on the actual site at Greenham Common where the protesters' tents were pitched years before. This particular sculpture marked the beginning of an important shift in my work towards site-specific outdoors installation or interventions. It extended my way of creating artwork beyond classic gallery spaces in mind and made me reassess the way we exhibit art in surroundings we don’t expect, and how different people engage with it. This project formed the basis of an extensive research of specific locations that challenge, interpret, and inform my work. This new way of working integrated a fresh direction of my own identity and creativity into my work and opened up communications and collaborations with other artists and organizations, which continues to shape and inform my work . The project that closely followed “Embrace the Base” was “Perishable Goods,” which was installed on the mountain above the Swiss Alpine resort of Verbier at the Alpine Sculpture Park of the Verbier 3D Foundation. “Perishable Goods” is a pallet of compressed flesh (again made from wood/wax/resin) bulging out, yet held together and at the same time, and adorned with luxury chains. With the impression of the work being crudely dropped on top of the mountain, installed for 5 years, the work suggests the intensity and intrusion of the change of population in Verbier in the winter months whilst referencing the stark contrast of the need for emergency aid food pallets dropped off in disaster zones. The sculpture slowly decayed over the period it was installed, like meat: The top fleshy wax layer melted away with the sun and revealed the underneath, more fleshy intestine layer which is resin and the gold chains started to rust. The photographs of your sculptures on the Swiss Mountains and Moroccan Sahara Desert evoke brilliant juxtaposition. How do you decide which sites are suitable for your artwork to inhabit? It’s a mixture of sourcing locations that fascinate me and liaising with arts organizations that could be interested in the project. For example, with ‘Perishable Goods Verbier’, I was invited to do an artist residency by the Verbier 3D Foundation. As part of my residency, I spent 6 weeks in the mountain resort of Verbier/Switzerland and one thing that struck me was that in the off-season, 4000 people are living there and in the winter season, the population increases to 40,000 people. I started to think about this number of luxury tourists…like they were compressed flesh which then resulted in creating "Perishable Goods" on site. During my time in Verbier, I also created another sculpture called "Avant/Aprés" which consists of a red carpet scenario in the mountain landscape with no indication which boundary is the VIP side to aspire to be or which one we may be held back from. The work touches on the seclusion, exclusivity, and hybridity of the mountain town of Verbier, famous for attracting luxury tourists. In relation to the "Mutation" theme of the artist residency; the work points at the lack of actual physical mutation and the desire to be different or transform. The intestine-like rope made of resin and wax, references the non-physical aspect of desire, highlighting the fact that underneath we are all the same. As I was looking for suitable locations to install the work, the idea for a video-installation developed and I filmed a video-piece depicting bizarre imagery of an unsuitably dressed luxury tourist in an evening dress and high heels walking around the Swiss mountain endlessly searching for the VIP area atop a Swiss mountain, lugging gold poles, a red carpet and an "intestine" rope. The video-installation Avant/Aprés embodies the desire to belong and aspirations of VIP-ness - the endless search for inclusion, climbing to reach the peak and the accompanying sense of exhaustion. The piece manifests the fundamental psychological need to belong, and the constructed culture of the exclusiveness of the ‘VIP’ which goes back to wanting to belong to a ‘tribe’, in this instance a very exclusive one. I developed the idea for “Perishable Goods No.5” two years later. In this instance, I sourced the desert location myself as I was looking for a site that stood in total juxtaposition to the Swiss Mountains. I worked with Next Level Projects, an arts organization here in the UK, to help with the logistics of installing the work in the Erg Chebbi desert in Morocco. Of course, with the desert heat, the wax melted away much quicker than its counterpart in Switzerland. Both locations are in stark contrast to each other, and both represented different challenges, but I was equally happy with how the work inhabits either of the two locations and how the surroundings inform its meaning differently. All art, especially yours, elicits some sort of response from viewers. What is your relationship to how your artwork is received, especially when you rely on the emotions of disgust and appeal? Is it the artist’s responsibility to care how their work is received?

Of course, I want people to engage with the work but I have no desire to have control over how people respond to the work and it is very interesting for me to witness people’s reactions. The reactions vary greatly—there are people who can’t look at these objects or feel nauseous. It’s fascinating how people are often repulsed by the abject quality of a sculpture, but also at the same time really want to touch it. It is that grey zone where desire and repulsion hover back and forth that I’m attempting to capture with my work. You’ve also created gold medical instruments that are all distorted in some way. What was the inspiration behind them? Do you see yourself working in materials other than wax? The gold medical instruments series work with the notion of the foreign intrusive pain-inducing object that becomes the body itself as it blurs the lines between inside/outside of the body and Self & Other. I particularly looked at medical instruments that are used during childbirth and how to “emotionalize” these cold, stark metal objects in contrast to the soft fluid body they invade, such as forceps that were first developed in the 1600s and where the design remains largely the same. I gold dipped these sculptures to play on the notion of desire and luxury, so for example ‘The Bvlgari Edition Forceps’ are adorned with diamantes and a tiny little luxury brand logo. Sometimes wax isn’t suitable for a specific commission, so I now often work with resin and incorporate less wax, or just an outer layer of wax. Saying that, wax is still my favorite material to sculpt with—it allows for flexibility and there is never an endpoint, so a piece can “rest” for months before I warm it up to work on it again. Years later, I still enjoy the ritual element of melting wax: the slow process, building up layer after layer.

0 Comments

|

Archives

April 2023

Artists

All

|