|

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Lex Brown is a multimedia artist who uses poetry and science-fiction to create an index for our psychological experiences as organic beings in a rapidly technologized world. Through humorous characters and expansive fictional worlds, her work opens up a place for spiritual examination. Brown has performed and exhibited work at the New Museum, the High Line, the International Center of Photography, Recess, and The Kitchen, REDCAT Theater, The Baltimore Museum of Art and at the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. Brown holds degrees from Princeton University and Yale University. She was a 2021 recipient of the prestigious USA Fellowship and is the author of My Wet Hot Drone Summer (Badlands Unlimited) and Consciousness (GenderFail Press). Her podcast 1-800-POWERS available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. What I find really unique about your work is that you explore many mediums like drawing, painting, print, sculpture, installation, and video in a very balanced and cohesive way. In my experience as an artist, I’ve always felt a pressure to find a niche and stick with it, but you’ve successfully cultivated art in all of your desired mediums. Why do you choose to create in a range of forms and when did you understand you didn’t have to confine yourself to a single artistic practice?

I have always loved making things in a lot of different ways. Especially right now, as I'm visiting my parents, there are little traces of that around the house—little storybooks that I would create and little fragments of songs. I always liked making a lot of things, but I didn't know that that was a path until I went to college and started learning about conceptual art. It was very exciting for me as a young person to see so many different artists use different media and underscore the material or the interaction with viewers. I've continued from there, developing ways to understand my own working in different media. On the one hand, it is kind of an outgrowth of whatever my expressive tendencies or intuition are at the moment—if I just feel like writing a song or making a drawing. But then, of course, I think about the viewer in the space. Using different media is a way for me to sculpt the experience of a space as a whole. I always think first and foremost about the space and about the interaction between the viewer and my work, which guides how I work in different media. It's also just dependent upon, as someone who works in performance and video, the way that different opportunities or collaborations come, which is slightly different than working in sculpture and working in painting. Some of it is dependent upon who I'm working with at the time and what ideas I have in my head for what's coming up next. Generally, as I'm working on a current body of work, I'm thinking about the ones that I want to make after that, and how I can already build in those connections as I'm working on the current body of work. Do your procedures for two and three-dimensional work differ from video or performance work? Do you have a preference working in a certain medium? I don't think I have a preference. Each medium has its own chemistry, its own sort of recipe. There's definitely a big difference working two-dimensionally compared to three-dimensionally. But as much as possible, I try to translate the same kind of affective mood that I have in my performance or video work into my two-dimensional work. When I'm writing something with characters, there's already so many different character voices and narratives in my head. Writing is a huge part of my practice and cuts through everything. A lot of the drawings and paintings I've made are text-based. My favorite process to work the most in is music because the way music guides me through it. Audio really clicks with my brain, so I love to write music and work with other musicians. The most fun part of my process is when I get to collaborate with other musicians. Speaking musical language is very magical. Video editing is also my favorite. I love the precision of it, but it can be very maddening. The result of a video is so gratifying because you can show a video anywhere. Each medium has its highs and its lows. For example, sculptures are so fun, but sculptures have a totally different life as a physical object. In comparison, time-based media doesn’t even exist until they're actually happening. Speaking about editing, is editing something you had to self-learn? I've had some teachers—the teacher who taught me the most about editing was Johannes DeYoung. But editing-wise, I've just edited for a long time and followed my sensibilities. Whenever I'm watching movies or television, I’m taking in everything, from the cuts, the cues, the setting. Over time, I'll return to certain compositions in editing. I tend to think about editing in terms of painting or collage. That’s so interesting to think about editing as collaging. I loved the storytelling and satire in Communication and I’m so amazed that it’s a one-woman show. Can you walk me through the process of creating that piece? Sometimes I start a performance piece with the costume before I write, but I’m not sure how Communication started. It's always hard to remember the beginning of something. I try to write scripts the same way that I write poetry, and then fit it into characters and develop some kind of plot. In this case, I knew I wanted to have a plot and I knew I wanted to be about communication. I think it started with that. The first section of the video is the characters sitting in the dark in the planetarium. The second kind of chapter is Wanda, the director of the planetarium and the third one is the character who's loosely based off of me, having a conversation on the phone. The phone call is about a relationship that I had been in. And I was like, how do I process this relationship without it being directly about my relationship, because the relationship was like too much for me to process. That’s a strategy I sometimes use—fictionalizing my real life into a story. It also might have started with that monologue or that I knew I wanted a character to be named Aspen vendor boss. My practice is very interdisciplinary, coming from all angles. I generate ideas from movement, from a costume, from sound. A monologue is pulling them together. I do think of my writing as being more related to poetry—the way I write is really based on sound, rhythm, and beats. A character or a plot point is a beat. I'm trying my best to write something that's coherent but there's always that part of me that is wanting to try different angles because inspiration keeps coming. Was Communication self-directed and self-filmed? It was self directed, but I worked with Joe Short and Andrew Gitchel at Harvard. Joe was filming me and Andrew was doing the lights. They also built the set pieces. But I wrote everything. I’ve done other projects where other people are performing and I really like to work that way as well. But at that time, when I was creating Communication, it was the first body of work that I had made after quarantine. I wasn't in a place to work with a lot of people. I felt like I really needed to kind of play around and do something that was loose, because when you're filming yourself and writing for yourself, you know exactly what you have to do, because you’re the performer. I know that if I'm the one who's performing it, I have no problem with doing 20 takes or trying 10 different versions. I have the freedom to be more flexible and experimental. If I have an idea or want to change the script, I don’t have to explain everything to others. That's the beauty of working solo. I’m enthralled in the very idiosyncratic storytelling that characterizes your video and performance work. Where do you find inspiration for these stories? I have so many sources of inspiration that it's hard to name a single one. I'm constantly watching TV shows—whether at my own house, or at somebody else's house, or even at the gas station. I love reading books and finding things on Pinterest. I take a lot from everything and my art is what comes out of it. In terms of video, I'm really inspired by a lot of comedy films by Steve Martin and Eddie Murphy in the 80s. Those films weren’t only funny, but contained political commentary. I think, especially in the 80s, there was a critique of corporate culture. The films of that era are really influential to me in terms of how I think about the stories I'm telling and how I want them to register to an audience. Another one of my greatest influences is Tracey Ullman, who had a sketch comedy show where she dressed up as different characters, some of whom people would now consider very problematic, but back in the 90s, we didn't even have the word problematic. Anna Deavere Smith’s work is also super influential to me. She is known for taking on different characters, generally characters people dislike, and reenacting their actions. Stew’s musical Passing Strange also really influenced me, inspiring Foccaciatown. Most of my influences are in TV and film, but I’m also inspired by certain stage performers who are more experimental. You frequently incorporate acting or music into your artwork. Do you have acting or music education? I actually am not formally trained in music, but I’be written and performed many songs. I did have acting training throughout my life, mostly in clown. Clown comes out of commedia dell'arte, which is Italian. And then all of the clown teachers that I have have come out of a they are from a pier goalie, a branch of clowning. Clown is a performance approach that is about playing with the audience. Rather than playing to the audience, the clown plays with the audience. Sometimes you wear a red nose or a costume, but a lot of times you don't. It's really about finding very universal and existential humor about life's highly profound and dramatic moments. In contrast to Communication, in Animal Static, you worked with a cast of actors. What was directing that like? It was really, really fun. I’m actually editing another collaborative project called Glass Eye, which I started in 2020. It's so fun working with other performers and with friends. For the Inside Room, I also worked with friends and other participants in the Recess Arts program. It's fun to write something and then just see what people do with it and how they improvise. Increasingly, I enjoy that more than performing myself. There are times when I really like to perform, but when it comes to the camera, I really have fun being behind the camera. You also host a podcast, 1-800-Powers! What prompted you to begin this podcast, what do you hope to accomplish with it, and where do you see it moving in the future? I started my podcast for so many reasons. I think first and foremost, because I really missed the performances that I was doing where I could talk to and with the audience. With COVID, the frequency and the length of my performances changed and I wanted some way to work that muscle and also practice writing. I just released the first episode with guest Delali Ayivor. It's a great way to have conversations with people who I respect and admire and share those conversations. I love working in audio and storytelling so much. I don't want to say too much because I don't want to jinx myself or anything. In the future, I would love to have more guests and to incorporate a variety show format. I would love to have syndicated segments on it, where somebody else would produce their own segment which becomes part of the episode. Eventually, in my life, I'd love to have a TV show. I have a lifelong desire to enter the world of television. Having a podcast is also a way for me to write episodes and just kind of finesse the format. But for this first year, I told myself to just see where it goes. It doesn't matter how long it takes me and it doesn’t have to be perfect. Whatever happens happens. It’s been great. I also love that podcasts are something that can be shared and listened to in the future, so I think about it as this addendum to my practice. That's so exciting! I hope you get a TV show. I love what you said in your conversation with Audra Wist back in 2015— “love as the essence of the universe, which is beautiful, but not peaceful. Each person is a universe, and you have to come to an understanding. Maybe real love is unexpectedly coming to the same definition of what love is.” You also read a beautiful passage from all about love by bell hooks in a podcast episode. Has your definition of love changed in the past years? How does love influence your work? I think I would still agree with that quote. I don't know if my understanding of love has changed. I think my relationship to love and my expectations of the type of love that I encounter with others has shifted. During the pandemic, there was a very intense time of intimacy, whether that was feeling extremely isolated or becoming closer with people in your life. I don't think of love as a primal motivating force in my work as much as I used to. I’m still sharing my universal love with the audience when I’m performing—it's not that I've become cynical or jaded or something. Love is still in my work, but I became a lot more interested in craft and focused on the practical side of love. Love to me is more action-based than thought-based. I really feel like I'm in a zone of action. My core values are still the same. I still want people to feel magic and feel transported and transcendental through my work. Through personal experiences, I have more experiential knowledge of the boundaries of love. But then, love, it's never-changing. It's never going to go away, especially between some of my friends who are such amazing friends. I’ve been thinking and feeling more about friendship, which to me is the ultimate love. To be able to be friends with your family or to also be able to be friends with somebody you love romantically is very important. Love shows up in projects like Animal Static, where I work with friends. Lastly, I have to ask about your books, Consciousness and My Wet Hot Drone Summer, which I feel are so distinct from one another. I’m fascinated by how Consciousness transcends form and tradition. Why did you decide to culminate your work into a book? Are you looking to publish more books in the future? Definitely! I have so many ideas. For Consciousness, Be Oakley, who runs GenderFail, a small publishing house contacted me and the book grew from there. It seemed like the right time. I had been working in a certain way and didn't have a documentation of my songs and projects. The book seemed like a great way to do that because the amazing thing about books is that they travel around the world. People would take photos of my books and send them to me. It’s also such a treat to do readings. I love working in books and text. There’s a couple of books that I want to write, but I just have to sit down and write them.

0 Comments

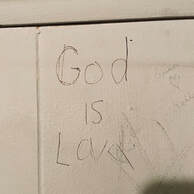

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Steven Espada Dawson is from East Los Angeles and lives in Madison, Wisconsin, where he is the Jay C. and Ruth Halls Fellow in Poetry at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing. The son of a Mexican immigrant, he is a 2021 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellow. His poems appear/appear soon in AGNI, Guernica, Poetry, and the Best New Poets and Pushcart Prize anthologies. I’m in awe of so many of the metaphors in your pieces. I remember reading “What I Hate Most About Mom” for the first time and being stunned by the lines “I see death everywhere. / A banana left / to the sun is a bat’s / cadaver.” What’s your process like for finding and crafting comparisons? I wrote that poem at a moment in my life of terrible negativity bias. When my speaker says, "I see death everywhere," it's because I saw death everywhere. The poet William Matthews writes, "I'm in these poems / because I'm in my life," and that rings loud and close for me. "What I Hate Most About Mom" was built around that bat image, actually. It's a real thing I witnessed. I remember seeing a banana peel someone threw on the ground in the parking lot outside my apartment. For whatever reason I didn't pick it up and went on to lock myself inside for a couple days. When I went out again it startled me. It was black and shriveled and very bat-like to me. I think our involuntary responses to images tell us a lot about how we're feeling. It's a kind of value-neutral alchemy where the world helps us understand ourselves better. I think I'm really no more witness to the world than any other creative person. What I will say is that I'm really good at stopping what I'm doing and writing things down. Sometimes I'm too good: interrupting conversations and phone calls. My friends are not huge fans of this approach. Yes, I relate to that so much! Being a writer is so much more than the act of writing—it’s also observing and irking your friends. Where are you recently turning to for inspiration? Thank you for that question. I haven’t been reading much of anything these last couple weeks, as I’m currently moving across the country. I did recently discover the work of Jay Hopler, and it's been keeping me afloat in all this uprooting. I feel like his work asks you to pinky swear with uncertainty in a way I haven't read exactly before. That gesture is a huge comfort to me right now. Here's the poem that initially got me hooked: "self-portrait not looking" (originally posted on Twitter by Brian Tierney). Aside from that, I've had the pleasure of seeing a lot of bathroom graffiti at truck stops on this 20 hour drive. It's tough to pick a favorite, but there was one on the bathroom wall of John's Food Center in Topeka, Kansas that really got me. Someone wrote "God is Love," and another person carved some additions, turning it into "God is Lava." Thank you for recommending that piece, it has such meticulous wordplay. In the same vein, every one of your poems also feels so carefully and thoughtfully crafted. Can you talk about how much time you spend on a piece, how you know it’s finished, and how you decide it’s ready to submit to publications?

I spend a lot more time "preparing" to write than I do actually writing. I'm diligent about archiving what I observe/experience, and that makes the actual writing process easier. I also daydream a lot about what any particular poem is going to look like on the page, so when it finally happens I've got a shape and line breaks in mind. Sometimes it feels like drawing a picture from memory. Then, I'll sit down at my laptop or my phone. (Side note: I wish I was cool enough to hand write my poems for cool-mysterious-poet points, but my handwriting is terrible.) The writing process might take a single draft or twenty after that. The poem you referenced earlier, "What I Hate Most About Mom," was written in 15-minutes in the bathroom of Major Restaurant in Indianapolis. A poem with similar themes, "Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Mother's Heart," took a couple years of drafts to get right--and I'm still not totally convinced. I'm finished with a poem when I feel like I can't learn anything from it anymore. Publishing is a byproduct I'm thankful for, but I write more to learn about myself, how I'm feeling, how I want to feel; if others find the poems helpful in learning about themselves, that's a huge bonus, and I'm grateful for their reading. When a poem has taught me what it can, it's "finished." Something that has taken a lot of pressure off of me is the realization that any particular poem might have multiple lives. A poem you wrote three years ago but never pushed on might find you while shuffling through your notes. It might turn into a brand new thing with wings, might be the centerpiece of your new collection. A poem you got published in a journal might look totally different in your book. Different title, form, ending. Might look a little different in an anthology down the road. Anyway, I don't think a poem is a fixed artifact, and that realization has helped me set more poems down, pick new ones up. No way, 15 minutes! I could think about the last lines for hours. That’s such a beautiful way to put revision. I’m thinking of what Ocean Vuong said in Lit Hub— “The poem is like a tree, and the book is a photograph of the tree. You take a photograph of the tree, but the next day, the tree has new cells. The next year, it has new branches. We have to make peace with the fact that a book is actually just a photo album, and that the organic psychic life of the poem is already growing somewhere else, somewhere inside you. And we pin it down.” I think you’ve pinned down your elegy series—“Elegy for the Four Chambers of My Heart/My Mother’s Heart/My Brother’s Heart”—so well. How does each elegy evolve from or interact with one another? Are you currently writing more elegies? I love that quote from Vuong, woah. Book as a photo album!! Thank you for sharing that. I've always been drawn to elegies. I think writing them teaches us the details of our love for someone. That idea of "love" can get really vague sometimes, so abstract in its own hugeness, and writing elegies can force you to point at the specific, not the boundaries of some idea. I've been thinking about writing another "Elegy for the Four Chambers..." poem for my biological father who was never in the picture. I think it'd have to be an erasure poem because of that, and I haven't found exactly the right text that needs to be erased. The series you point to was especially difficult to get down because of the circumstances each elegy orbits. My brother really is/was an addict who disappeared suddenly 13 years ago. My mom really is at the end of her beautiful and difficult life. As someone who often struggles to manage depression and suicidal ideation, I sometimes feel at the end of my own life. I'm writing these elegies for people that exist at the fringes of their living. In this space, the poems feel like both levies and testimonies. Something to build up, to prepare for the grieving to come. Something that helps me understand the value of what will be lost. You teach writing for the Austin Library Foundation, Austin's Youth Poet Laureate Program, and Ellipsis Writing! What’s your best piece of writing advice? I'm lucky to work with a ton of incredible writers. Seriously, my students inspire me to write more than books do. I find that a lot of my students, though, are writing specifically to publish their work/submit to contests/etc. This is one of myriad weird ways capitalism has t-boned art for many people. It's become just another talent for people to prove their academic worthiness or something. I've been there--and in some ways I still am--and I respect the hustle, really. But I think that forced mentality is a good way to keep writing the same poems over and over. It's an easy way to plateau your craft and, more importantly, the figuring out you're doing every time you write. I think, if they can do it safely, new writers should write towards discomfort. Take risks with your work while you're still chisling out your voice. When you eventually publish at your favorite places, that extra work will be well taken by readers. You mentioned in The Rumpus that you’re finishing a manuscript. Can you tell us more? I'm in the final stages of my first full-length collection, tentatively titled Elegy, Pending. It's a book about a lot of things but primarily a family caught in the liminal space just before death. I'm currently at work on the last poem (fingers crossed) that the book needs to feel like itself. I'll be spending the next nine months as a poetry fellow at the University of Wisconsin - Madison, where I plan to finish this collection, work my way into a second, and begin a super-secret nonfiction project I've been daydreaming into existence. |

Archives

April 2023

Artists

All

|