|

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Maia Cruz Palileo (b.1979, Chicago, IL) received an MFA in sculpture from Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY (2008) and BA in Studio Art at Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA (2001). Palileo has had solo exhibitions at the Kimball Arts Center, Park City, UT (2022); the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, CA (2021); the Katzen Arts Center, Washington D.C. (2019); moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2019); Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, NY (2018); Taymour Grahne Gallery, New York, NY (2017); and Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, New York, NY (2015). Palileo has been featured in recent group exhibitions at The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC (2023); National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. (2022); Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA (2022); San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA (2022); Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (2022); The Rubin Museum of Art, New York, NY (2018); and the Bureau of General Services Queer Division, New York, NY. Forthcoming exhibitions include a group exhibition at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE (2023). Their work is in the collections of The San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA; The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC; The Speed Museum, Louisville, KY; and The Fredriksen Collection at the National Museum of Oslo, Norway. Palileo is a recipient of the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program Award, NY (2022); NYFA Painting Fellowship (2021); Jerome Foundation Travel and Study Program Grant (2017); Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Artist Grant (2014); Astraea Visual Arts Fund Award (2009); Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant (2018); and Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA Award (2008). Palileo has participated in residencies at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Madison, ME; Lower East Side Print Shop, NY; Millay Colony, Austerlitz, New York; and the Joan Mitchell Center, New Orleans. Palileo's solo exhibition, Days Later, Down River, is on view from April 1 to May 20 at Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago, Illinois. Congrats on your solo exhibition Days Later, Down River! Art takes on different roles depending on its curation and position, and for this exhibition, you decided to incorporate a banig. How do you hope to contextualize the banig in this exhibition? The banig is the central object in the exhibition. When you walk into the gallery, it's the first thing that you see.The banig is loaned from the University of Michigan. It was an object that I had encountered when I was there back last May when I was doing research. I wanted to incorporate something from that collection for a couple reasons. One of them was to fold it into the show and have it be in a centralized location. Traditionally, a banig is a handwoven mat used for sleeping on. A woman probably hand wove it, and it’s probably been sitting in the archival collection for a long period of time. I don't know when the last time it was touched by human hands or taken out of its drawer. Part of me wanted to just take it out of the archive and bring it to the public. While I've known about Michigan’s collection for many years, I had never seen it because it isn’t all that accessible. I wanted to give it a different context, have people have a chance to see an object from the collection, and recontextualize it as an object that is made for rest and for gathering. I'm thinking about that in terms of coming together around the object, but also resting as a memorial to the people who made that banig or the people who it was taken from. Museums can be very painful sites to marginalized communities because they are intimately tied to colonization. The U-M Museum, as many museums around the country have, has developed exhibitions that exploit, exclude, or misrepresent marginalized groups. How do you feel about the University of Michigan housing so many artifacts from the Philippines, and do you believe they should be repatriated? I have a lot of feelings on this topic. I wish there was a simple answer to that question. On the one hand, because of these archives, I'm able to experience these objects and learn this history in a tactile and physical way by going to the museum and immersing myself. At the same time, like you said, it's not easy. Artifacts have been completely contextualized in a harmful way. I wish there was an easy fix for it. What's interesting is that while I was in Michigan, I learned that there’s really no legal structure around these collections. For this collection, it's very difficult to trace the creators of these objects or identities of human remains because they’re so old. I can't say that I'm an expert on it. I've spent some time in this vast, vast, and insane place. What I think about in my work is what does spending time in a place like that do to the body and especially a body that I'm in? How do I digest what I've seen because I can't unsee it? How do I, as an artist, present that research through my work? Thank you for understanding the need for representation in the arts, especially accurate representation that is not simplified and generalized from a Western gaze. Who or what spurred you to approach art as a way to recontextualize your history and defy the single narrative that white America has manufactured? I appreciate being asked this question because 20 years ago, when I was making paintings of my aunties and my grandmas, this was not a question that was being asked. I know it was a conscious decision to paint people from my family, but to be honest, back then this conversation was not being had in my graduate school critique sessions. I needed to find something that I felt deeply connected to and what that ended up being, in the beginning and still today, were my familial connections and experiences of loss, death, grieving, and memory. Those themes are personal, and they're also familial and historical. In examining my own family ties and my own longing to connect with departed family members, I was led to do a lot of research. I was going through the archives and I saw people who were photographed in these archives. They had this kind of knowing look in their eyes that I was searching for something that I could connect with. What I saw in the photographs and what I chose then to represent in my paintings was resilience, which went counter to the narrative that has been written about all these colonial photographs. They didn't describe the fierce look in someone's eye; they were the opposite. It was interesting to see something that I saw in the pictures and then to read what was written about it because they were completely opposing. I took these figures and removed them from this context and put them into a new context, which I guess it's similar to the banig, which I took out of the archive. But, on the other hand, the banig is torn and has creases and shows its wear and tear over the years. The archival images are similar. They still carry the residue of all the years they’ve been housed in the archives. You describe yourself as a multi-disciplinary artist. How do you decide if a work will be two-dimensional on paper, a painting, or three-dimensional? A lot of times the work will sort of show itself in a form. I don't always know what the content of the work will be, but when I start to visualize a show or a work, it comes to me in its form. I might know that I want to make a huge painting or something on a smaller scale. Usually I start with the smaller scale. I'll start to work out formal ideas and color schemes. It's a little similar to making a collage where I'm pulling imagery from the archive and putting it into a small painting, and then those small paintings are transferred into a larger painting. For this show, I also had the sense that I wanted to transform the space completely. That's how the installation came about with the sculptures and the light projection and the banig. I've had an obsession with ceramics for many years, but I never really took the leap. This year, I was able to take the leap and I joined a clay studio. I took some classes and it just stuck. Deciding what medium I use is almost like pulling a tarot card in the morning and just asking for guidance and saying, what should I do today? What does my heart feel like doing today? Do I feel like going to the clay studio or do I feel like painting today? Sometimes I don't have a choice. I don't have that luxury if I have a deadline. But a lot of the work that I was making for the show started with me asking, where does my heart feel connected to today? I also don't see much of a difference between the mediums. They all feel like words in the same sentence. You accessed your family’s history through relying on oral storytelling and archives. How did these forms of research combine to inform your artwork? Very slowly and circuitously. Sometimes, when I’d read a story in folklore and something would sound familiar, I would ask somebody in my family about it and they wouldn’t know. But then I'll remember later I’ll get a flicker and remember like a story my dad had talked about or I’ll remember something that makes a connection. The connections happen after the work is made, which is a little bit spooky. Sometimes, while I’m in the process of making an artwork, a friend might visit my studio and talk about what I’m thinking about. Those friends might have experiences with what I'm researching and that was the case for this body of work. I had found a photo album of these two mountains that were near the province where my father's family is from in the Philippines. I was in Michigan with another artist who had been to this sacred mountain. He shared all his pictures and research with me, which was amazing. I also have an auntie who's like my mentor. She teaches me about ancient Filipino script and Filipino spirituality. She had mentioned this mountain to me before I went to Michigan, so I had known about it. I was already talking to people about it, and then I found it in the archives, and then I talked to them again. Or sometimes, someone in my family will see a painting and it'll trigger a memory and they'll tell me a story. When my grandmother was alive, I just used to ask her a million questions and she would tell me stories. I do have letters that she wrote and, and I ask other people for their memories too. That's not as fruitful compared to going straight to the source. I think the oral history thing is collective because without my mom being alive, there’s so much I can’t access. I can’t ask her, but I can ask my uncles, but they also have other stories that I don't know if my mom would know those things. How much time did you spend researching in the archives before beginning to create these artworks? 2017 was the first time I really spent day after day in an archive at the Newberry Library in Chicago. I spent a couple days at the Field Museum. I was in Chicago for about a month every day in the summer. Then, in Michigan, I had a two-week fellowship, which doesn't sound like a lot of time, but it was intensive. I got back from Michigan at the end of May last year and started using the research I did. But I’m still processing all of it—what I saw in Chicago, what I saw in Michigan. I'll probably be processing it forever and I'll probably go to another archive and then be processing that. You lost your mother at a very young age. How did you process and overcome that overwhelming amount of grief when you were only a teenager, and has her absence impacted your artistic work?

Art got me through it. When she passed away, I was still in college and I was taking art classes and I just ditched all my other classes and went to the art studio every day. That got me through. Obviously, it’s been 24 years now and I still miss her. She’s always been a big motivation for my art. I felt a sense of longing and became interested in family because of her absence. I wanted to learn more about her. I think it's that kind of drive that has propelled me to look into my personal family history, which I wasn’t thinking much about before. In other ways, her death gave me a feeling of freedom to become an artist because she never believed that being an artist could be an actual job. My dad, on the other hand, has always been supportive. He gave me my first camera, which is how I got into art. He was always supportive, but he was also a little bit less prominent in my rearing. My mom really set the tone for the family. Her death helped me take that step and explore my interest in art, in my gender identity, and in my sexuality—in all the stuff that we had butted heads about. It's not that they didn’t remain an issue after she died, but I think there's many ripples that came from her passing. I really can't say enough how art is a container for grief. Art is immense and I'm very grateful for that. In Ligaiya Romero’s American Masters documentary about you, you mentioned how you couldn’t come to terms with your sexuality growing up. How have you departed from those feelings of shame as you’ve grown up? I'm living my life. I found other people who’ve also had to grapple with that, and they're living their lives and they're happy. Finding a community was huge. Falling in love with someone who is awesome and exciting and going ahead with it anyway even if I wasn't sure if people would approve was huge. Living in New York is helpful. I also just went to a lot of therapy and times have changed a lot. Iit was really different back then, and I don't think I realize what a relief it is today to be able to walk around on the streets and not be yelled at or harassed. I know that there's a lot still going on, but for me, it has become a lot better over the past 25 years. How has your artistic practice and craft transformed since you began painting? I didn't go to school for painting, so the fact that I even started painting was a huge transformation for me. I was mostly focused on sculpture and installation. In 2012, I just had this overwhelming voice that was telling me to paint, even though I didn't think that I could switch lanes because when I was in graduate school, everybody except for me and one other person, who was in the sculpture department, was painting. So we were constantly talking about painting, and I hated painting, and yet I was doing it secretly. Honestly, once I actually listened to that voice and I went through all the growing pains of trying to learn how to paint—making really ugly paintings and grappling with oil paint and all that stuff—everything started to go the way I wanted it to go. A lot has changed. I think painting is really hard to do because I never think I can make another painting after I've finished a set of paintings. But then suddenly, there's another body of work that's been made. Now I'm back to making sculptures. Like I said, I try not to distinguish too much between the different mediums, but I will say I think there's something about painting for me that just keeps me coming back. I'm always a little bit mystified about how my paintings come together, and I think there is something about painting in particular that can communicate the same mystifying experience to somebody looking at the painting. I don't know if that's the same case with making an installation or a sculpture where everything is measured out and I already have the sketch of what it will look like and I just have to execute that vision for me. With painting, I'm not executing a vision. I have no fucking idea where it's going.

0 Comments

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Jane Wong is the author of two poetry collections: How to Not Be Afraid of Everything (Alice James, 2021) and Overpour (Action Books, 2016). Her debut memoir, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City, is forthcoming from Tin House in May 2023. A Kundiman fellow, she is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize and fellowships and residencies from Harvard's Woodberry Poetry Room, the U.S. Fulbright Program, Artist Trust, the Fine Arts Work Center, Bread Loaf, Hedgebrook, Willapa Bay, the Jentel Foundation, and others. She is an Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Western Washington University. Congratulations on How to Not Be Afraid of Everything! It’s such a well-crafted, tenacious, and rich collection and resonated so deeply with me, having come from very similar experiences. “Everything” is one of my favorite poems of all time. I was really proud of myself for understanding the Chinese characters. How did “Everything” develop? What does the word “everything” connote to you?

That means the dumpling-filled world to me that my book resonated with you, thank you! "Everything" is definitely a central poem in the collection, especially since it's referenced in the title. I wrote this poem inspired by my dear friend and fantastic poet Chen Chen. He has a poem called "Poem in Noisy Mouthfuls" and at the end of that poem he writes: "No, I already write about everything --" and begins to list his "everythings." I teach this poem often and have my students write through their "everything"s (the themes, questions, things, people, creatures, etc. that keep coming back to them). And I knew I had to do it myself! These are my obsessions-- from language loss to my mother to my gambling father to the constant gaze of toxic white men. I am illiterate in Chinese and I only have a beginning/intermediate grasp of Cantonese. So, hilariously, I had to google translate the Chinese -- which I think some readers of Chinese might notice! It's a kind of inside joke -- that I had to do that. It makes the line "Sometimes I dream in Cantonese and I have no idea what is being said" even more haunting I think. Visually, the book is broken up into six sections, which are each divided by a page with an illustration of a wave. At every consecutive section divider, the wave seems to be retreating and finally, the collection ends with an illustration of a moon. Can you talk about the visual creation of How to Not Be Afraid of Everything? Love this question! I have the design team at Alice James to thank for the beautiful interior, as well as the cover artist Kimothy Wu. I knew I wanted this artwork from Kimothy for the cover, thinking about that almost-touching moment between the girl and the lion. I fell in love with that terror and awe, this possibility of falling into the lion's maw. It feels both terrifying and startling. I also loved the color -- what I like to call "intestinal pink." That feels so right for all the guttural imagery in the book -- and all the writing about food! I really loved how this lion also lives in a kind of galactic space--- space waves. And, as you write, there's so much constant retreating in the section dividers -- how the space waves move across through time (the intermingled past, present, future). I love how the design time included a moon at the end, a kind of mirror/reflection moment. I felt like it was that moment of touching my ancestors! I love that! The collection contains a great deal of imagery related to animals and the natural world—boar, rat, snake, worm, moss, mud, beet, etc. How does nature influence you and your work? It took me, surprisingly, a long time to notice how many creatures show up in my writing. I'm a bit obsessed with the strange underworlds of our environment -- especially creatures and flora that tend to get overlooked. I love slugs, rats, and mud. I really love low tide and getting my feet in the mud -- and the anemones that spring up in their green-pink glory. I feel like animals have these rhythms all their own -- and I've always wanted that kind of interior knowledge. Like, how does a worm know that I don't? It's funny because I grew up in a strip mall -- surrounded by parking lots and cement. But there were ants and pigeons and worms and accidental cilantro patches too. It's all nature! Sections of “When You Died” have appeared in Foundry and Underblong. How did you decide on the final version to include in this collection? I think of "When You Died" as a long, serial poem--- which can be hard to publish as one cohesive whole! I sent along excerpts to wonderful journals like Underblong and they did such a great job of retaining its singular, yet cohesive story. I knew I wanted to have this long poem in the center of the book, as its own section, but I didn't necessarily know the order of these sections yet. I think of this poem as an epistolary, a long letter, to my ancestors who didn't survive the Great Leap Forward. I wanted to collapse time, to reach my hand to the other side of their world--- and feed them the tomato soup I was eating while researching this time period. I knew I wanted to end that poem with an opening -- with a bowl cracking open. That opening portal ends up being the last poem in the book, "After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly." In that poem, my ghosts actually reply to "When You Died," which feels like a kind of magic I still have a hard time finding words for! Speaking of researching, you’ve mentioned that you couldn’t research your history through interviewing your family. How did you access the history that you discussed in How to Not Be Afraid of Everything? Ooh, this is a tough question because it was pretty hard to research a history that is censored. There was a great deal of propaganda during the Great Leap Forward -- so much so that the numbers of deaths due to famine are continually contested (ranging from 15 million to 55 million). I primarily referred to Yang Jisheng's Tombstone, which was so fundamental to uncovering what happened during that time to my family -- his book is also deeply personal. It was a hard book to read and to be honest, I couldn't fully "read" it. I had to read a few pages and walk away. It was emotionally too difficult. While I couldn't speak directly to my family about what happened, I did listen very closely to what they did tell me -- in between moments of silence, i.e. why I'm not allowed to waste food. How my grandfather was adopted by a man in the village, who lost his family. This close listening -- like tuning your ear toward the center of the earth -- was central in personal stories of such deep trauma. Thank you for sharing that. Silence is as significant as substance in many of your poems. In “MAD,” you ask readers to fill in the silence. How have you come to accept and act against cultural and familial silence, as well as the silence of Asian and Asian American history from Western education? Thank you for reading "MAD" so closely-- that poem is such an important one for me, thinking about rage and resistance. As the poem starts, it asks the readers to fill in the silence via mad libs, but then it gets progressively harder to avoid the word I want you to use (i.e. "you have big eyes for a ___"). There's anger in these expectations, in constantly being defined through the white gaze. It was a really long journey for me in terms of speaking out and demanding to be seen. The thing is, I never learned about my own history; Asian American history is so often left out of our formative education. I didn't have an Asian American literature class in college or graduate school. The first time I taught an Asian American studies class, I cried over the copy machine; the class I was teaching was also the class I always wanted to take. Whenever I teach Asian American literature, it's incredibly emotional -- for me and my students. For them, it's the first time they've ever heard of Angel Island poetry. It's ten weeks of writing/art by Asian Americans -- beyond that one token book they read in high school (often, when I ask my undergrads to name a book by an Asian American writer on that first day, some of them say Memoirs of a Geisha.. which is written by a white man. This is how silenced we are). It is absolutely central to me as a writer and as a teacher to be in resistance together. That this is not just Asian American history, it's American history everyone should know. Questions permeate through this collection. You end with the poem “After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly,” which is filled with compelling questions. What role does questioning serve in your words and life? Thank you for this beautiful question about questions! Poetry, for me, feels like a space where questions are fundamental. Poetry refuses clarity to a certain degree; that's what I love about it. The open-endedness of it, the question that leads to another question, the liminal space of not knowing (yet getting slightly closer). With that particular poem, I kept thinking about the questions as a means of communication—of what my ancestors would ask me. How would I answer? Is my answer also a question for them? Questions feel bewildering, yet they make me unearth what I thought was solid... I guess questions feel like excavation. Especially when it comes to my silenced history, I feel like I had to ask questions—and be open to the lack of answers. Thank you so much for creating "The Poetics of Haunting," which is such a necessary and luminous project. How long did the project take? Do you see yourself extending this academic work? Thank you so much for exploring this project! "The Poetics of Haunting" website is part of my dissertation--which explores the haunting impact of migration, war, and empire on the work of Asian American women poets -- generations after. While my dissertation is a monograph book, I really wanted a public scholarship/digital aspect--to reflect what each poet wanted to share in terms of haunting. I was so lucky to be able to speak to Don Mee Choi, Pimone Triplett, Diana Khoi Nguyen, Cathy Linh Che, Bhanu Kapil, Sally Wen Mao, Christine Shan Shan Hou, Monica Sok, and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha (from afar/across the spiritual/earthly world). And I gave each poet multiple options to respond with their ephemera. Bhanu recorded a kind of meditative altar offering. And Cathy shared family photographs. It was so moving! This particular digital humanities project took a year and half, but the dissertation took about three. I'd really love to return to this book one day, and find more creative ways to intertwine my creative and scholarly loves! I’m so excited for Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City! Can you tell me more about your upcoming memoir? I'm both excited and nervous about my memoir, as this book feels super vulnerable -- and of course, writing in a different genre is nerve-wracking. The memoir is out on May 16th next year, via Tin House. I like to think of it as a love song for Asian American immigrant babies who grew up low-income and working class. There are lots of stories of growing up in a restaurant, about illegal dental care in New York City, and my father's gambling addiction. There's also a lot about hypersexualization as an Asian American woman-- and how I can't separate where I come from from my intimate experiences. My mom is a big thread throughout, thinking of her as the true poet in my ancestral line! I hope the book is funny and weird and felt. And I hope I made baby Jane proud -- who, in part, I wrote this book for. INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Noʻu Revilla is an ʻŌiwi poet and educator. Born and raised with the Līlīlehua rain of Waiʻehu on the island of Maui, she currently lives and loves with the Līlīlehua rain of Pālolo on Oʻahu. Her debut book Ask the Brindled (Milkweed Editions 2022) was selected by Rick Barot as a winner of the 2021 National Poetry Series. She also won the 2021 Omnidawn Broadside Poetry prize. She has performed throughout Hawaiʻi as well as in Canada, Papua New Guinea, and the United Nations. Her poetry has been adapted for theatrical productions in Aotearoa as well as exhibitions in the Honolulu Museum of Art and the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. She is a lifetime “slyly / reproductive” student of Haunani-Kay Trask. Learn more about Noʻu at nourevilla.com. Brandy Nalani McDougall called your work “poetry…for the gut…Oiwi poetry at its finest and fiercest.” What initially drew you to poetry? Why turn to poetry as a vehicle to solidify and defend familial history?

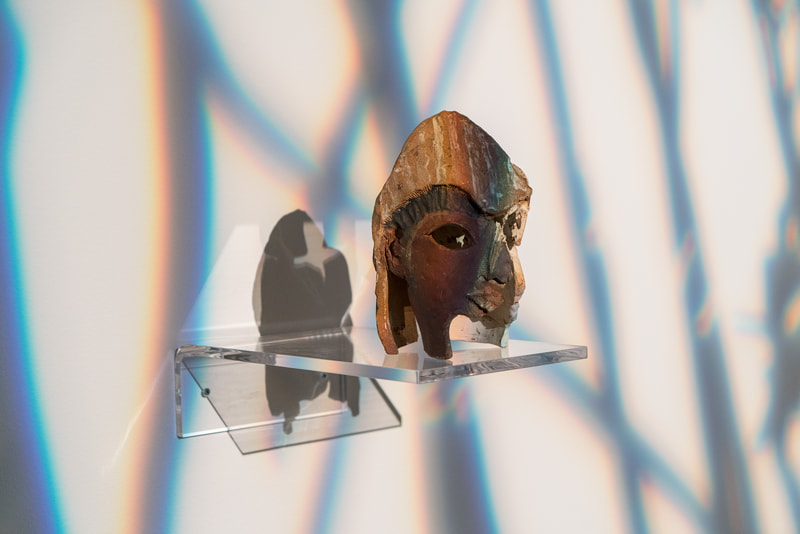

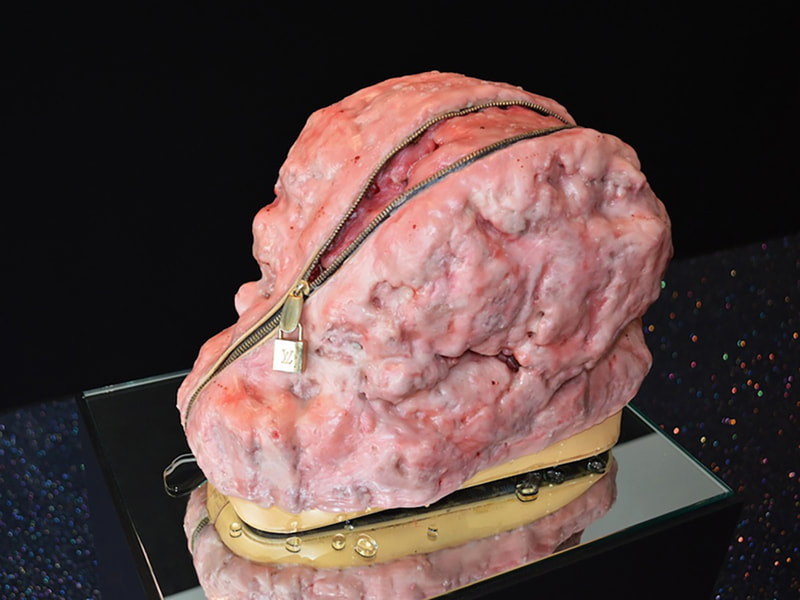

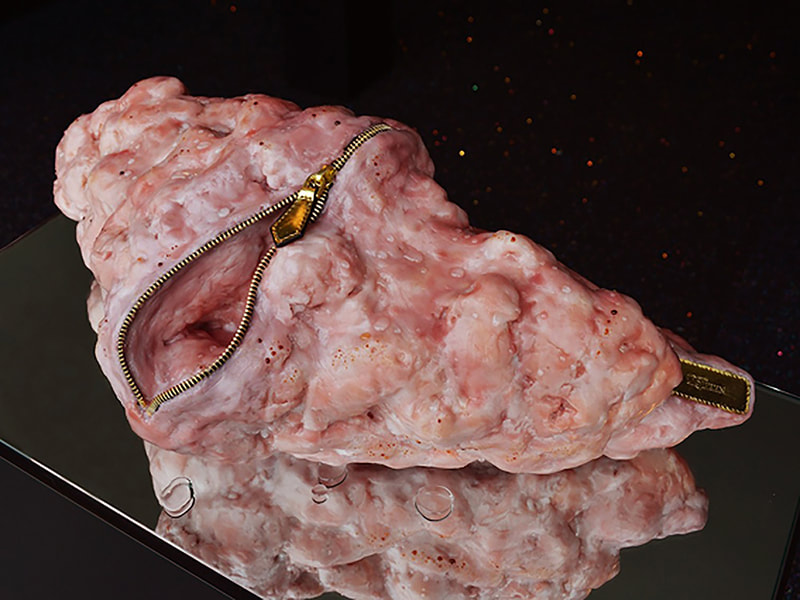

I appreciate your choice to say: defend. Poetry, for me, exacts a closeness. In my early 20s, it was a transformative closeness that called me out on a lot of bullshit. I kept imitating dead white men because that’s what was put in front of me and I didn’t know how to reach for anything different. Representation matters. At the time, I had just enrolled in a workshop with Robert Sullivan, a Māori poet, and we had a meeting to discuss my first poem of the semester. The draft was loaded with allusions to Greek mythology so I thought it checked all the “right” boxes. Yet with the hard copy of my poem in hand, he looked me in the eyes and asked: “Where is your culture? Where are your people?” No preambles, no cushion. I will always be grateful for how naked those questions were because I couldn’t hide. My culture was nowhere in that draft so essentially where the fuck was I? Every day poetry keeps me honest; it tests me, he alo a he alo (face to face). After so long in the closet and centuries of American colonization working every day to vanish who and what and how I love, I want to work toward closeness. Thank you for sharing that. I’m so glad that those questions were asked. I read that you learned Ōlelo Hawai‘i in your 20s. Why was acquiring this language necessary for you and how did it impact your work? Language is continuity. I feel closer to my lands and waters and ancestors when I’m able to wrap my mind around the world the way they did. In Hawaiʻi, for example, each place has names for their winds and rains, which means my kūpuna (ancestors) devoted time and observational rigor to studying how these elements shaped the land and its people. Clearly, for them, this kind of attention was valuable. So the names my kūpuna composed not only reflect a deep study of their environment but also a deep respect for the relationship between kanaka (people) and ʻāina (land). Naming practices reveal a lot about a relationship, especially in Hawaiʻi, and that’s what so much of poetry is, the responsibility of naming, renaming, or remembering names. Speaking of imitating dead white writers in your previous answer and the responsibility of poetry as memory, which writers influenced you to cease this imitation and harness poetry to defy tradition and memorialize your ancestry? It’s not so much defying tradition, as if there is just one, but choosing to feed and be fed by other traditions. Right now my students and I are talking about the multiple and simultaneous, the many-named and many-bodied in terms of literary genealogy and futurity. When I think of this kind of work, I reach for writers like Leanne Simpson, Joy Harjo, and Audre Lorde. Indigenous Pacific women writers like Sia Figiel, Tusiata Avia, Teresia Teaiwa, and Selina Tusitala Marsh absolutely devastated me when I first started taking my poetry seriously. Their work broke me open. It had to...I forgot I was part-ocean. I loved the conversation and connection between you and Jocelyn Kapumealani Ng in “letters to the gut house: collaboration & decolonial love in Hawaiʻi.” Why did you decide to write an essay together in epistolary form? Thank you so much for reading our collaboration, Sophia. Your aloha for that piece means a lot to me. Jocelyn is my collaboration soul mate and we’ve been writing letters to each other for years. When we get together, the worldbuilding that happens is fearless and tender. As a queer ‘Ōiwi femme who descends from shapeshifters, that balance is important. So on the way to AWP in 2019, I started writing a thank you letter to Joce for all the ways our collaborations have fed me. That six-hour flight was one hundred percent gutspill and I ended up presenting the letter on my panel. I came home and read it to her on the beach in Waikīkī, then she wrote me a letter in response, then I wrote again, then she wrote, back and forth – gratitude inspires reciprocity. The essay that Milkweed published weaves fragments of different letters we have written to each other. You could say it’s a little bit of light from different rooms in our gut house. That spontaneity is so precious. You’ve dedicated several of your poems to younger family members. How do they inspire and inform your work? The manuscript of this book really turned when I realized that it wasn’t enough to just write against what I wanted to burn down—violence against Indigenous women, rape, homophobia, colonization. It can’t just be about what we help bring to an end. We also have to commit aloha to growing new ground. What are we helping to build? I write to my three nieces because I want them to know they are part of larger and longer conversations between Indigenous wahine who show up and protect each other. Wahine like myself, their mother, their grandmother, their great-grandmother, their other aunties, and people like Haunani-Kay Trask and Brandy Nālani McDougall. What I went through, I want that shit to stop with me. So I name each violence, I set them out in the sun. I want my nieces to see that ʻŌiwi women can name injustice without looking away, from ourselves or each other. Yet it’s important that these poems also enact joy, play, and gratitude. I want my nieces to see aloha as intergenerational action. How do you approach performing your poems? How does performance amplify the written word? Performance is a vital part of my practice. I’m lucky to be part of a close-knit creative community here on Oʻahu. During the pandemic, it was nourishing to lean on each other and share how much we missed performing for live audiences and talk each other through how dramatically our writing rituals changed. For my book launch in September, the entire lineup was chosen family, and one wahine in the audience came up to me after and said it felt like she got to watch best friends fall in love with each other. High praise indeed. I’m always thinking of different ways to share poetry in public. Lehua Taitano blew my mind one year at AWP—she cracked the world open for me as a performer. For some years now, Jocelyn Ng and I have been building toward a project that is part art installation, part immersive spoken word. I also want to figure out how to afford feeding audiences every time I share my work. It may seem like a small thing but when people are able to share good food, good drinks, and good story, intimacy deepens. In an interview with The Rumpus, you said, “Words have legs. I like thinking that those who know ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi are able to follow those legs into a part of the poem that is just for them. And that part of the poem is just as active as any other part because people who can enter there can talk shit with me, commemorate with me, sing the song with me, even call me out on something missing or out of place.” Do you write with an intended audience in mind? Yesterday was our Lā Kūʻokoʻa, our Hawaiian Independence Day, and in the early hours of that same day, Maunaloa erupted! We call this a hōʻailona, or a sign in this case of great change to come. Hulihia. When lava flows, it's a good time to reflect on the changes we’ve made in life and what we want to grow moving forward. It feels appropriate to talk about audience as lava makes its way to the ocean on Hawaiʻi island. My ʻāina, my lāhui, my kūpuna, my ʻohana, they are always with me when I write. And I don’t feel it as a burden; it is a responsibility and privilege. I want to write to them, for them. Ask the Brindled is my humble way of reaching out to other Indigenous women, especially ʻŌiwi wahine and women who fall in love and choose to build family with other women. The book is also a love letter to survivors and shapeshifters. Thank you for taking the time to speak with me and for such stunning answers. Lastly, as a professor, how do you teach poetry as a resistive and reclamatory force? My students and I talk about poetry and ea, or breath. Ea also signifies rising and sovereignty in my language. What do we give our ea to? How do we earn the ea of our readers? How do we bring our bodies to meet and metabolize the poems we write? Poetry should be part of the body, and our bodies are here on purpose. My ancestors worked hard to make sure I’d be here, with you, with my communities, with every reader who chooses to make story with me. We are here on purpose. INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU While his work has a clear figurative language, the large-scale paintings of Juan Miguel Palacios contain a strong conceptual load, where his work developed in series, and has a constant wandering of the individual's identity and its relationship with the environment. Concepts such as mourning, duel, luxury, restlessness, and inequality are constants vital in his work. Juan Miguel Palacios continually explores the complex range of human emotions with a free, powerful, and always modern technique. He is driven by the search for new forms of expression and fuses sociopolitical themes with personal experiences and historical antecedents of art, creating a unique and modern environment on the most outstanding and controversial issues of contemporary society. Canvas, vinyl, methacrylate, aluminum, and drywall are surfaces where Juan Miguel Palacios presents his shocking and extensive work. Born in Madrid in 1973, Juan Miguel Palacios begins to paint at the early age of 6 years. After a long journey with many art professors and Fine Art schools, at age 12, he joined the studio of the renowned Spanish painter Amadeo Roca Gisbert (disciple of Joaquin Sorolla) for six years. Along those years, he was educated and formed in a strict academic training until he joined the Faculty of Fine Arts in Madrid in 1991. When he had completed his college degree, in 1997, he founded the Laocoonte Art School of Madrid. During this period, he combined mentoring and teaching with the development of his artist career. Currently, he resides in NY since 2013, showing his work around the world. The image of the pig is a common theme throughout your work. Where did this interest stem from?

In general, the theme of animals has been quite recurrent in my work, always as metaphors of what I want to express. For example, for many years I worked with the image of a hyena as a symbol of oppression within an increasingly unequal society. This has been a central theme of my work for the last few years. On this occasion, for the development of the new series "Un final feliz," the pig seemed to me the perfect figure for the new narrative that I wanted to present. The pig is an animal that has been present in all cultures. It is loaded with strong symbolism, loved and revered by some and hated by others. An animal that pleases and amuses us but at the same time we dislike and disgust it. In Spain, where I am originally from, it is present in all our gastronomy, which we consider delicious but, at the same time, it is always present in our insults. That duality and contradiction itself is what really interested me in addition to its great visual load. Texture plays a role in many of your pieces, adding dimension and depth. How is texture important to your practice and how do you go about choosing a certain medium for a piece? Texture plays a very important role in my work. For me, it is another fundamental element in the practice of painting, just like color. I cannot conceive a piece of art without color even if texture is absent. Whether the texture of a piece is flat or smooth is intentional. As you were saying, in many of my paintings I not only use texture to create dimension and depth, but also to create narratives that I cannot achieve by just drawing or painting in a conventional way. For example, texture can generate optical illusions that confuse the viewer and force a more careful look. In this way, the materials and mediums that I choose for my works play a very important role. For example, for my "Wounds" series, the use of drywall to create broken wall effects was vital. Fundamentally, this series talks about inequality. In my opinion, women have suffered the greatest injustice and inequality in the history of humanity. In such a manner, I was creating female faces that had been or were being assaulted. I was painting on a first layer of transparent vinyl and then superimposed on a second layer of broken drywall. The broken parts of the wall represented the scratches and wounds produced by the aggression. In a metaphorical way, I wanted to create an analogy between the wall and the woman. Something so hard, strong and resistant, but subjected to constant aggression ends up breaking. The drywall became a key part of this series. The combination of lightness and cleanliness of the transparent vinyl with the roughness and hardness and depth generated by the broken drywall, like the combination of something more illusory such as the paint strokes and the realism of the pieces of the broken wall create a confusing effect on the viewer at first glance. Something that was very attractive to me as they were such strong and evident images. In short, depending on what I want to tell and express, I use different materials. I found the use of negative space in Assaults so compelling. Can you speak about the process behind and the interaction between those works? Something that always interests me to do in my work is transferring a concept I want to communicate into a form of representation. For example, if I'm talking about the concept of aggression or abuse, I will try to carry this abuse or aggression by hammering and burning the wall, throwing turpentine on the canvas, scratching the paint, or removing it with paint remover. For these works, I used transparent vinyls as the surface and synthetic enamels as the medium. Enamel, an oil-based paint, dries faster than oil paint. So by the time the painting was done, between 30 minutes and an hour later, the first sketch lines were already practically dry. By throwing the solvent to deform the paint, I was removing much of the paint except for those first preparatory lines that were almost dry, thus leaving large empty spaces. That concept of absence was really interesting for my discourse because every time that there is an aggression, there is an empty space. A fissure impossible to fill. Something that was, and will never be again. You depict a variety of faces and personalities, especially in The Wanderers and Emociones. Where do you find your subject matter? The topics that I work on are usually based on what I am living or thinking at every moment. The things that worry and concern me or the issues that I want to denounce. My daily walks and especially my train commute to the studio are usually moments of reflection and inspiration for all the thoughts I wanna communicate. The New York subway is that magical place where everything is possible. You can practically find all kinds of social classes and cultures in a very small space. When I arrived in NY, I remember being utterly in love and enraptured by everything—every single image I saw, each aspect and scene. But above all, of every single person and the immense diversity of them. The richness of this scenario itself was presented to me with splendid beauty. But as time passed, with a further and deeper look, behind that superficial beauty, I started to notice the loneliness behind it. Gazes of sadness and melancholy, faces with no expression. They represented a kind of theatrical stage full of wanderers in the kingdom of heaven. New York is a city that welcomes hundreds of thousands of people, attracted by its splendor and wealth, every year with the sole objective of having a better life or success. But as everyone knows, it is a very tough city. A city in which everyone arrives with great energy; but as time goes by, the city wipes out and frustrates illusions, generating wanderers trapped in a lonely city. This type of appreciation was, for example, the origin of the Wanderers series. What an empathetic and tender origin story—I feel so similarly to your depiction of New York. Your artwork is humongous! What is it like in the studio working with such large-scaled work? Working at a large scale is what I love the most and where I really find myself. The physical act of painting becomes movement and dance. My thoughts move at the same rhythm as my body and they both connect with my deepest emotions. It's where everything is fast and the paint falls off. Drips and spills get everything stained and the studio itself becomes an extension of the paintings themselves. Hazard is part of the creative process in the most remarkable way. In short, it is where the walls of my studio exude happiness. The problem with large and heavy formats is that your body pays a toll and it wears and tears over time. I am still recovering from my third major spinal surgery. What are you currently working on? The last series that I worked on before undergoing my last back surgery was Un final feliz, a series of works that were more fresh and fun. It was a social and political critique, especially of the American culture, sarcastically tinted with ironic overtones since everything revolves around the iconography of two pigs procreating at the foot of a collapsing town. The series is much more colorful than the previous series and has a greater tendency of abstraction, which is where I am heading at the moment. Precisely at this very moment, I'm moving my studio to a bigger place after 10 years in the same location since I moved to NY, which symbolically represents a big change for me that I hope will also be reflected in my work. I have the feeling that great things are gonna happen there. Stay tuned. INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Lucy Zhang writes, codes, and watches anime. Her work has appeared in The Molotov Cocktail, Interzone, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and elsewhere. She is the author of the chapbooks HOLLOWED (Thirty West Publishing, 2022) and ABSORPTION (Harbor Review, 2022). Find her at https://kowaretasekai.wordpress.com/ or on Twitter @Dango_Ramen. The first piece of yours I came across was "Money Baby," where the writing, reading, coding, and sound effects come together so ingeniously. How did "Money Baby" develop and how did you realize writing and coding could form such a perfect union?

“Money Baby” was actually part of a series of different pieces (many of them interactive) I did inspired by children or babies in non-human forms, so I guess I was already on a roll. The editors of Superstition Review told me I could do something creative with the recording, so it was their prompting that sparked the idea with the coin rattling audio. Ultimately though, I just wanted to explore money as a means of defining worth, livelihood, family, and nurturing. In terms of writing and coding, I had always been interested in generative art and would often code interactive visuals—visualizing music, playing with ARKit, etc. I decided “why does it just have to be art? Can’t it be writing too?”—probably because I was tired of whatever story I was working on that day and wanted a break. Fun things come from procrastination. That’s amazing! I wish such fun ideas came from my procrastination. Your interactive/digital work is simply so brilliant. I especially love “Heat death didn’t stop us from being shut-ins,” “Saplings,” and “Backspace.” How did these ideas originate, especially since they’re all so distinct and individual? I think the more I want to procrastinate, the more interesting my creative work becomes…which is not so good for all the tasks I’ve yet to complete. :P I wrote/coded all three of those pieces during the “height” of the pandemic, when everyone was still quarantining. It certainly felt like a rather apocalyptic, introspective time. “Heat death didn’t stop us from being shut-ins” and “Backspace” evolved from too much introspection as well as my adjacent novel research surrounding space, the universe, and physics. “Sapling” was part of that series of pieces I did on non human babies (in the same line of thinking as “Money Baby”, “Neuron”, etc.). I think “Sapling” originated from me just wanting to implement plants that grew using the JavaScript Canvas API. I really wasn’t thinking about any text or story or message at that point, hah! For most of these pieces, I explored and discovered and developed the content as I built the actual thing, so it’s hard to really pinpoint an origination beyond “hey Lucy is thinking again.” How do you maintain a writing schedule while also working as a software engineer? Does your day job influence your writing? I’m not sure I can call it a schedule. If I don’t write frequently enough, I begin to feel this growing sense of dread that doesn’t go away unless I pound out two to three thousand words (or so). This happens about once a week. Work has gotten rather busy lately which means less time for writing, so I’ve been feeling that dread more frequently. Can I call this Dread-Driven Writing? DDW? Maybe if you ask me six months from now, I’d have a different answer, but right now, work life is on fire which means writing life is also on fire (metaphorically). The influences from my day job are pretty straightforward: I like to write about technical things, engineers, robots. Sometimes these influences manifest in different ways, but ultimately it all comes down to expressing the geek inside. Thank you for that honesty, Lucy. I feel the same dread. I love your project I CAN SEE YOU WRITE. Can you take me through the process of collaborating with another writer? The process is actually quite simple! Sometimes the writer will already have an idea for something interactive, but they aren't certain what's quite possible, or maybe they have no idea beyond an inkling of potential for a certain piece. They'll send me the piece in text form, and I'll run off with my creative liberties. I'll do a lot of experimentation and have anywhere from a 50% complete to a 99% complete project. Then I'll send over an implementation of what I have with any open questions. From there, we'll iterate. Congrats on Hollowed and Absorption! Two chapbooks in a year! How does it feel? I’m honored that Thirty West Publishing and Harbor Review had faith in my works and published them. It’s also a very nice feeling to see my friends who don’t care much at all about literature holding copies of my chapbook. Also, prior to the chapbooks, I never put much time into collecting all of my individual pieces, so with these publications, I have a new-ish interest in actually doing something with once write-and-forget-about stories 😆 I’m curious if Hollowed and Absorption were created with each other in mind. You use the word “hollow” or “hollowed” in the pieces “Jiaozi,” “The Carriage Became A Pie,” and “Teach Me All There Is to Know” in Absorption. They weren’t! I don’t think that far ahead in life, hah. I think that’s more a result of me gravitating toward similar themes and emotions. :) Absorption contains a lot of scientific word choice. Can you speak about this decision to employ detailed scientific language to discuss themes of life and death? I often find it relieving to look at abstract concepts in extremely clinical terms. When I approach heavy topics from a more scientific lens, I start fixating on the engineering bits of how something works. It's easier for me to visualize and get excited about something that I know will have an answer if I look deeply enough as opposed to something as nebulous as death. Going back to your project I CAN SEE YOU WRITE, I love that you wrote “The sky and JavaScript is the limit.” What’s next for you? How do you see yourself continuing to push the limit of interactive and interdisciplinary art? I've been working with some folks on new projects but those have been taking their sweet time because the salary-earning job has begun to leave me with negative energy levels at the end of the day. That being said, I have ideas and really want to work on more long running projects connected by a theme of some sort. Maybe I'll get hacking away again during Thanksgiving break :) INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Young Joo Lee is a multimedia artist from South Korea, currently living and working in Cambridge, MA and Los Angeles. Lee holds an MFA in Sculpture at Yale University (2017) and a Meisterschueler degree in Film at the Academy of Fine Arts Städelschule Frankfurt (2013). In her recent moving image works, Lee's personal narratives as an immigrant, South Korean, and a woman interweave with the current and historical narratives to investigate the issues of alienation, discrimination, and mental illness in late capitalist society. Lee’s works have been exhibited at the Alternative Space Loop- Seoul, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art- Seoul, The Drawing Center-New York, Museum of Modern Art, Zollamt - Frankfurt, Curitiba Biennial, and GLAS animation festival, among others. Lee completed several artist residencies including Macdowell (US), Sanskriti Foundation (India), MeetFactory (Czech Republic), and Incheon Art Platform (South Korea). She is currently a Harvard Film Study Center fellow She currently is a Visiting Lecturer in Animation and Immersive Media Art at the Department of Art, Film and Visual Studies at Harvard University. She was a College Fellow in Media Practice at Harvard University (2018-20), a Fulbright Scholar in Film & Digital Media (2015-18) and a recipient of DAAD artist scholarship (2010-12). Her work is represented by Ochi Projects, Los Angeles. Lizardians combines animation, writing, music, and dance into such a compelling story. I loved that you included a watercolor painting of a panel on your website. It’s always so cool to see how artists arrive at their final piece. What was the process like behind creating Lizardians and working with a production team and cast?

Lizardians took quite a long time. I wrote the script in 2016 and it was supposed to be a live-action film. I was working with a writer and had many iterations and changes in the script, which changed the story a lot. But in the end, I ended up not working with the writer for the final version. When I finally received the funding to produce the film in April 2020, the pandemic had just started, so I had to adapt my plan to make it into a live-action film. That’s when I started to wonder if I could make it into a 3-D animation. I had already interviewed many of the actors and wanted them to represent themselves as characters. I used software to create facial features using the photographs of the actors. For the main character, I wanted her to be a part of my process. I took on the role as if I was doing a performance piece. I started writing the story after I encountered the stories about Foxconn, the Taiwanese electronic device manufacturing factory in China. The working conditions there were horrible and some of the workers committed suicide around 2010. This coincided with incidents at Samsung’s factories, in which workers were exposed to chemicals used in some of the electronic devices. Most of the workers were young women and many experienced miscarriages, unknown illnesses, and some even cancer. Some of them passed away due to that. In 2010, these two issues were happening at once and the way that these companies dealt with these problems were strikingly similar. Foxconn, for example, did not acknowledge that they knew about this, even though it would’ve been really hard for them not to. They were trying to push the responsibility of this elsewhere instead of addressing it. Samsung similarly denied the correlation, saying that it’s difficult to track the illness because it develops over a long period of time and that these people already had conditions before they entered the company. The battle between the families of the victims and the company took 10 years, until finally the families were acknowledged and received compensation for the deaths of their family members. These kinds of stories really made me think a lot about the relationship between an individual and corporations that have their own systems of logic and operation. I think it’s almost impossible for individuals to understand or penetrate into the systems of corporations. Their stories melt away. As someone who has multiple electronic devices and uses them daily, I thought about the loss of the trace of the labor that goes into making those devices. The name value of an iPhone or MacBook has value in society and presents the corporation's image, hiding the other stories of the labor and effort that go into making those products. I was imagining a situation where this not only applies to electronic devices, but many other products that we use. We don't really see how these products are made or who made them. What if a product is recognizable as an individual's labor and time? In Lizardians, the product that Shelby produces is her own body parts. Because we turned the film into 3D animation, there was another layer of dealing with the loss of human human touch and the labor behind the images. It was quite a lengthy process, taking about one year. Every scene was acted out via Zoom. I was directing them over Zoom and then using the footage for the final animation. I would say Lizardians is the most complex project that I've made. I also noticed that in the Lizardians and Shangri-La exhibition brochures, you included Korean and an English translation. Why was it necessary for you to include translation and incorporate both languages? I was born in South Korea, but I moved thirteen years ago. The exhibition took place in Korea, so most catalogs are bilingual. The funding came from Seoul Arts Foundation and the Harvard Film Study Center, which contributed to the bilinguality. How to eat a bar of milk chocolate is one of your pieces that I felt was directly and overtly political. How did the inspiration to film that performance arrive? That was quite a spontaneous performance piece. I found this chocolate bar at the JFK Airport on my way back to LA. At the time, in 2018, Donald Trump was the president and I just had to buy one because it was just such a bizarre product. The chocolate bar was an object that recorded the present time and I just wanted to get one for myself. I didn't know what to do with it. It was standing in my studio for a while and I was just thinking about it. I think I was renewing my visa back then and the process was quite stressful due to the increased anti-immigrant sentiment all over the news. I was building up frustration and anger to this figure and I thought of eating the image and what it represents. In a way, it’s a way to attack, but at the same time, I digested it because it's chocolate. I think that was kind of my way of dealing with what I was feeling at the time. Chocolate is a sweet thing, but the image on it contrasted with that sweetness. I think that contrast is interesting given the history of chocolate. Chocolate was used during war. M&Ms, for example, were invented as an emergency food that wouldn’t melt in soldiers’ pockets. Chocolate was also one of the first things that were introduced to Korea by the United States. I’m also curious about the drawings you display on your website and the text that accompanies some of them. Are those drawings in series with one another? How does drawing play a role in your work in other media like performance and animation? Some of them loosely connect to each other and some stand alone. Drawing and writing are how I start brainstorming my work. A lot of the drawings are expanded into stories and are snapshots of bigger narratives. Some of those I developed into film or video works. Drawings for me are more intuitive. They contain what I’m thinking about or what I'm encountering and experiencing. I try to unpack my drawings to see if I can develop them into longer stories. I think drawing becomes the foundation for what I'm going to make next. Text is sort of hard to explain. As I draw, I write and sometimes they come together. For example, for the drawing of a woman giving birth to a wardrobe, I felt that I needed the sentence for the drawing to be complete. You studied art at Yale, The Academy of Fine Arts in Germany, and Hongik University. Can you talk about what it was like learning in three different countries? In Korea, I created a foundation for my artistic practice. I tried out everything. I was primarily doing painting, but most of my professors were male and in a certain age group, so they didn’t like my approach to painting. That made me pivot to non-painting mediums. I think it has changed a lot now, but when I was in school, I still dealt with that conservatism as a woman. For example, one professor would say that most of us female students would marry and never make art again. That really got to me. I became very interested in social issues and what constructs personal experience, and what made me become who I am, or how I perceive other people or myself. I began searching for female artists who I could connect and look up to because of the lack of examples that I saw around. That led me to go to Germany. I lived in Germany as a child for three years, so it wasn't a totally foreign place. I had some unresolved feelings about living there. I had great, but also traumatic experiences and I wanted to revisit that. Germany also just has really nice art museums and support for artists. It’s a very artistically-rich country. The German school system is totally different. The school I went to was almost like a residency. There were no formal classes and only a meeting once a week, so I had a lot of free time. This was really good for me because I didn't want classes at the time. I just wanted to make things and be in an artists’ space. It was more practical learning how to survive as an artist and be independent. The reason why I came to the US was firstly because I received the Fulbright Scholarship. Otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to afford coming to the US. I had been feeling tired of feeling like an outsider in Europe. I think the diversity in the US, especially in cities like New York, made me think I could live and work here. I was going to go to film school initially. All the other places that I applied to were film schools. But the reason why I went to the sculpture program was because of the similar freedom I craved when I was in Germany. Because of my multimedia tendencies—wanting to do sculpture, film, and performance—the cross-disciplinary and multimedia approach at their program seemed more fitting. My two years at Yale were great—I was exposed to screenwriting and other classes that I couldn't take when I was in Germany or in Korea. I had the opportunity to take the skills that I gained to come up with new ideas. I found it really fascinating what you said in your interview with Women Cinemakers about the future of women in interdisciplinary art: “there are more female students than male students in art schools, while there are more male artists in museums and galleries. It means that the situation changes for the female students when they graduate…” Your work deals with otherness in a historical and personal context. How have you coped or responded to being othered in your artistic and non-artistic life? It’s changing a lot. I’m seeing a lot of positive change both in the United States and in Korea. I’ve been teaching at Harvard for the past four years and I think I combat this by giving more opportunities to female students. I would never discriminate against male students, but I’m more conscious of the difficulties that female, nonwhite, or international students experience and I’m mindful of that when I’m teaching. Recommending students what to do and providing resources and information to them as much as possible is really important to me because it’s something I didn’t receive. That’s how I want to change this, on top of the work I make and stories I tell and uplift that raise awareness and promote underrepresented groups. Your fellowship and your collaboration with the other Media Practice Fellows Margaret Rhee and Sohin Hwang sounds so exciting! How did this group come about? Do you all take inspiration from each other’s work? That was from 2018 to 2019. I received the College Fellow in Media Practice Fellowship. We were the first cohort—Margaret, Sohin, and I—and we collaborated on many things, but most importantly, we held a panel on women, mobility, and technology to promote women in technology, because women are still underrepresented in technology. All of our work, even though we’re in different fields, address similar themes and concerns. It was very exciting that we crossed paths and had this opportunity. INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Lex Brown is a multimedia artist who uses poetry and science-fiction to create an index for our psychological experiences as organic beings in a rapidly technologized world. Through humorous characters and expansive fictional worlds, her work opens up a place for spiritual examination. Brown has performed and exhibited work at the New Museum, the High Line, the International Center of Photography, Recess, and The Kitchen, REDCAT Theater, The Baltimore Museum of Art and at the Munch Museum in Oslo, Norway. Brown holds degrees from Princeton University and Yale University. She was a 2021 recipient of the prestigious USA Fellowship and is the author of My Wet Hot Drone Summer (Badlands Unlimited) and Consciousness (GenderFail Press). Her podcast 1-800-POWERS available on Spotify and Apple Podcasts. What I find really unique about your work is that you explore many mediums like drawing, painting, print, sculpture, installation, and video in a very balanced and cohesive way. In my experience as an artist, I’ve always felt a pressure to find a niche and stick with it, but you’ve successfully cultivated art in all of your desired mediums. Why do you choose to create in a range of forms and when did you understand you didn’t have to confine yourself to a single artistic practice?