|

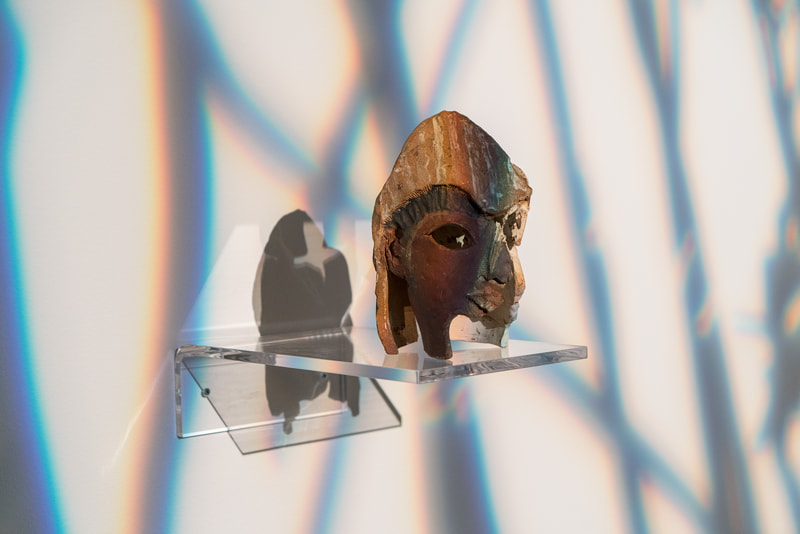

INTERVIEWED BY SOPHIA LIU Maia Cruz Palileo (b.1979, Chicago, IL) received an MFA in sculpture from Brooklyn College, City University of New York, Brooklyn, NY (2008) and BA in Studio Art at Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, MA (2001). Palileo has had solo exhibitions at the Kimball Arts Center, Park City, UT (2022); the CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco, CA (2021); the Katzen Arts Center, Washington D.C. (2019); moniquemeloche, Chicago, IL (2019); Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, NY (2018); Taymour Grahne Gallery, New York, NY (2017); and Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space, New York, NY (2015). Palileo has been featured in recent group exhibitions at The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC (2023); National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. (2022); Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA (2022); San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA (2022); Jeffrey Deitch Gallery, Los Angeles, CA (2022); The Rubin Museum of Art, New York, NY (2018); and the Bureau of General Services Queer Division, New York, NY. Forthcoming exhibitions include a group exhibition at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE (2023). Their work is in the collections of The San Jose Museum of Art, San Jose, CA; The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, NC; The Speed Museum, Louisville, KY; and The Fredriksen Collection at the National Museum of Oslo, Norway. Palileo is a recipient of the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program Award, NY (2022); NYFA Painting Fellowship (2021); Jerome Foundation Travel and Study Program Grant (2017); Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Artist Grant (2014); Astraea Visual Arts Fund Award (2009); Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grant (2018); and Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA Award (2008). Palileo has participated in residencies at Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Madison, ME; Lower East Side Print Shop, NY; Millay Colony, Austerlitz, New York; and the Joan Mitchell Center, New Orleans. Palileo's solo exhibition, Days Later, Down River, is on view from April 1 to May 20 at Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago, Illinois. Congrats on your solo exhibition Days Later, Down River! Art takes on different roles depending on its curation and position, and for this exhibition, you decided to incorporate a banig. How do you hope to contextualize the banig in this exhibition? The banig is the central object in the exhibition. When you walk into the gallery, it's the first thing that you see.The banig is loaned from the University of Michigan. It was an object that I had encountered when I was there back last May when I was doing research. I wanted to incorporate something from that collection for a couple reasons. One of them was to fold it into the show and have it be in a centralized location. Traditionally, a banig is a handwoven mat used for sleeping on. A woman probably hand wove it, and it’s probably been sitting in the archival collection for a long period of time. I don't know when the last time it was touched by human hands or taken out of its drawer. Part of me wanted to just take it out of the archive and bring it to the public. While I've known about Michigan’s collection for many years, I had never seen it because it isn’t all that accessible. I wanted to give it a different context, have people have a chance to see an object from the collection, and recontextualize it as an object that is made for rest and for gathering. I'm thinking about that in terms of coming together around the object, but also resting as a memorial to the people who made that banig or the people who it was taken from. Museums can be very painful sites to marginalized communities because they are intimately tied to colonization. The U-M Museum, as many museums around the country have, has developed exhibitions that exploit, exclude, or misrepresent marginalized groups. How do you feel about the University of Michigan housing so many artifacts from the Philippines, and do you believe they should be repatriated? I have a lot of feelings on this topic. I wish there was a simple answer to that question. On the one hand, because of these archives, I'm able to experience these objects and learn this history in a tactile and physical way by going to the museum and immersing myself. At the same time, like you said, it's not easy. Artifacts have been completely contextualized in a harmful way. I wish there was an easy fix for it. What's interesting is that while I was in Michigan, I learned that there’s really no legal structure around these collections. For this collection, it's very difficult to trace the creators of these objects or identities of human remains because they’re so old. I can't say that I'm an expert on it. I've spent some time in this vast, vast, and insane place. What I think about in my work is what does spending time in a place like that do to the body and especially a body that I'm in? How do I digest what I've seen because I can't unsee it? How do I, as an artist, present that research through my work? Thank you for understanding the need for representation in the arts, especially accurate representation that is not simplified and generalized from a Western gaze. Who or what spurred you to approach art as a way to recontextualize your history and defy the single narrative that white America has manufactured? I appreciate being asked this question because 20 years ago, when I was making paintings of my aunties and my grandmas, this was not a question that was being asked. I know it was a conscious decision to paint people from my family, but to be honest, back then this conversation was not being had in my graduate school critique sessions. I needed to find something that I felt deeply connected to and what that ended up being, in the beginning and still today, were my familial connections and experiences of loss, death, grieving, and memory. Those themes are personal, and they're also familial and historical. In examining my own family ties and my own longing to connect with departed family members, I was led to do a lot of research. I was going through the archives and I saw people who were photographed in these archives. They had this kind of knowing look in their eyes that I was searching for something that I could connect with. What I saw in the photographs and what I chose then to represent in my paintings was resilience, which went counter to the narrative that has been written about all these colonial photographs. They didn't describe the fierce look in someone's eye; they were the opposite. It was interesting to see something that I saw in the pictures and then to read what was written about it because they were completely opposing. I took these figures and removed them from this context and put them into a new context, which I guess it's similar to the banig, which I took out of the archive. But, on the other hand, the banig is torn and has creases and shows its wear and tear over the years. The archival images are similar. They still carry the residue of all the years they’ve been housed in the archives. You describe yourself as a multi-disciplinary artist. How do you decide if a work will be two-dimensional on paper, a painting, or three-dimensional? A lot of times the work will sort of show itself in a form. I don't always know what the content of the work will be, but when I start to visualize a show or a work, it comes to me in its form. I might know that I want to make a huge painting or something on a smaller scale. Usually I start with the smaller scale. I'll start to work out formal ideas and color schemes. It's a little similar to making a collage where I'm pulling imagery from the archive and putting it into a small painting, and then those small paintings are transferred into a larger painting. For this show, I also had the sense that I wanted to transform the space completely. That's how the installation came about with the sculptures and the light projection and the banig. I've had an obsession with ceramics for many years, but I never really took the leap. This year, I was able to take the leap and I joined a clay studio. I took some classes and it just stuck. Deciding what medium I use is almost like pulling a tarot card in the morning and just asking for guidance and saying, what should I do today? What does my heart feel like doing today? Do I feel like going to the clay studio or do I feel like painting today? Sometimes I don't have a choice. I don't have that luxury if I have a deadline. But a lot of the work that I was making for the show started with me asking, where does my heart feel connected to today? I also don't see much of a difference between the mediums. They all feel like words in the same sentence. You accessed your family’s history through relying on oral storytelling and archives. How did these forms of research combine to inform your artwork? Very slowly and circuitously. Sometimes, when I’d read a story in folklore and something would sound familiar, I would ask somebody in my family about it and they wouldn’t know. But then I'll remember later I’ll get a flicker and remember like a story my dad had talked about or I’ll remember something that makes a connection. The connections happen after the work is made, which is a little bit spooky. Sometimes, while I’m in the process of making an artwork, a friend might visit my studio and talk about what I’m thinking about. Those friends might have experiences with what I'm researching and that was the case for this body of work. I had found a photo album of these two mountains that were near the province where my father's family is from in the Philippines. I was in Michigan with another artist who had been to this sacred mountain. He shared all his pictures and research with me, which was amazing. I also have an auntie who's like my mentor. She teaches me about ancient Filipino script and Filipino spirituality. She had mentioned this mountain to me before I went to Michigan, so I had known about it. I was already talking to people about it, and then I found it in the archives, and then I talked to them again. Or sometimes, someone in my family will see a painting and it'll trigger a memory and they'll tell me a story. When my grandmother was alive, I just used to ask her a million questions and she would tell me stories. I do have letters that she wrote and, and I ask other people for their memories too. That's not as fruitful compared to going straight to the source. I think the oral history thing is collective because without my mom being alive, there’s so much I can’t access. I can’t ask her, but I can ask my uncles, but they also have other stories that I don't know if my mom would know those things. How much time did you spend researching in the archives before beginning to create these artworks? 2017 was the first time I really spent day after day in an archive at the Newberry Library in Chicago. I spent a couple days at the Field Museum. I was in Chicago for about a month every day in the summer. Then, in Michigan, I had a two-week fellowship, which doesn't sound like a lot of time, but it was intensive. I got back from Michigan at the end of May last year and started using the research I did. But I’m still processing all of it—what I saw in Chicago, what I saw in Michigan. I'll probably be processing it forever and I'll probably go to another archive and then be processing that. You lost your mother at a very young age. How did you process and overcome that overwhelming amount of grief when you were only a teenager, and has her absence impacted your artistic work?

Art got me through it. When she passed away, I was still in college and I was taking art classes and I just ditched all my other classes and went to the art studio every day. That got me through. Obviously, it’s been 24 years now and I still miss her. She’s always been a big motivation for my art. I felt a sense of longing and became interested in family because of her absence. I wanted to learn more about her. I think it's that kind of drive that has propelled me to look into my personal family history, which I wasn’t thinking much about before. In other ways, her death gave me a feeling of freedom to become an artist because she never believed that being an artist could be an actual job. My dad, on the other hand, has always been supportive. He gave me my first camera, which is how I got into art. He was always supportive, but he was also a little bit less prominent in my rearing. My mom really set the tone for the family. Her death helped me take that step and explore my interest in art, in my gender identity, and in my sexuality—in all the stuff that we had butted heads about. It's not that they didn’t remain an issue after she died, but I think there's many ripples that came from her passing. I really can't say enough how art is a container for grief. Art is immense and I'm very grateful for that. In Ligaiya Romero’s American Masters documentary about you, you mentioned how you couldn’t come to terms with your sexuality growing up. How have you departed from those feelings of shame as you’ve grown up? I'm living my life. I found other people who’ve also had to grapple with that, and they're living their lives and they're happy. Finding a community was huge. Falling in love with someone who is awesome and exciting and going ahead with it anyway even if I wasn't sure if people would approve was huge. Living in New York is helpful. I also just went to a lot of therapy and times have changed a lot. Iit was really different back then, and I don't think I realize what a relief it is today to be able to walk around on the streets and not be yelled at or harassed. I know that there's a lot still going on, but for me, it has become a lot better over the past 25 years. How has your artistic practice and craft transformed since you began painting? I didn't go to school for painting, so the fact that I even started painting was a huge transformation for me. I was mostly focused on sculpture and installation. In 2012, I just had this overwhelming voice that was telling me to paint, even though I didn't think that I could switch lanes because when I was in graduate school, everybody except for me and one other person, who was in the sculpture department, was painting. So we were constantly talking about painting, and I hated painting, and yet I was doing it secretly. Honestly, once I actually listened to that voice and I went through all the growing pains of trying to learn how to paint—making really ugly paintings and grappling with oil paint and all that stuff—everything started to go the way I wanted it to go. A lot has changed. I think painting is really hard to do because I never think I can make another painting after I've finished a set of paintings. But then suddenly, there's another body of work that's been made. Now I'm back to making sculptures. Like I said, I try not to distinguish too much between the different mediums, but I will say I think there's something about painting for me that just keeps me coming back. I'm always a little bit mystified about how my paintings come together, and I think there is something about painting in particular that can communicate the same mystifying experience to somebody looking at the painting. I don't know if that's the same case with making an installation or a sculpture where everything is measured out and I already have the sketch of what it will look like and I just have to execute that vision for me. With painting, I'm not executing a vision. I have no fucking idea where it's going.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2023

Artists

All

|